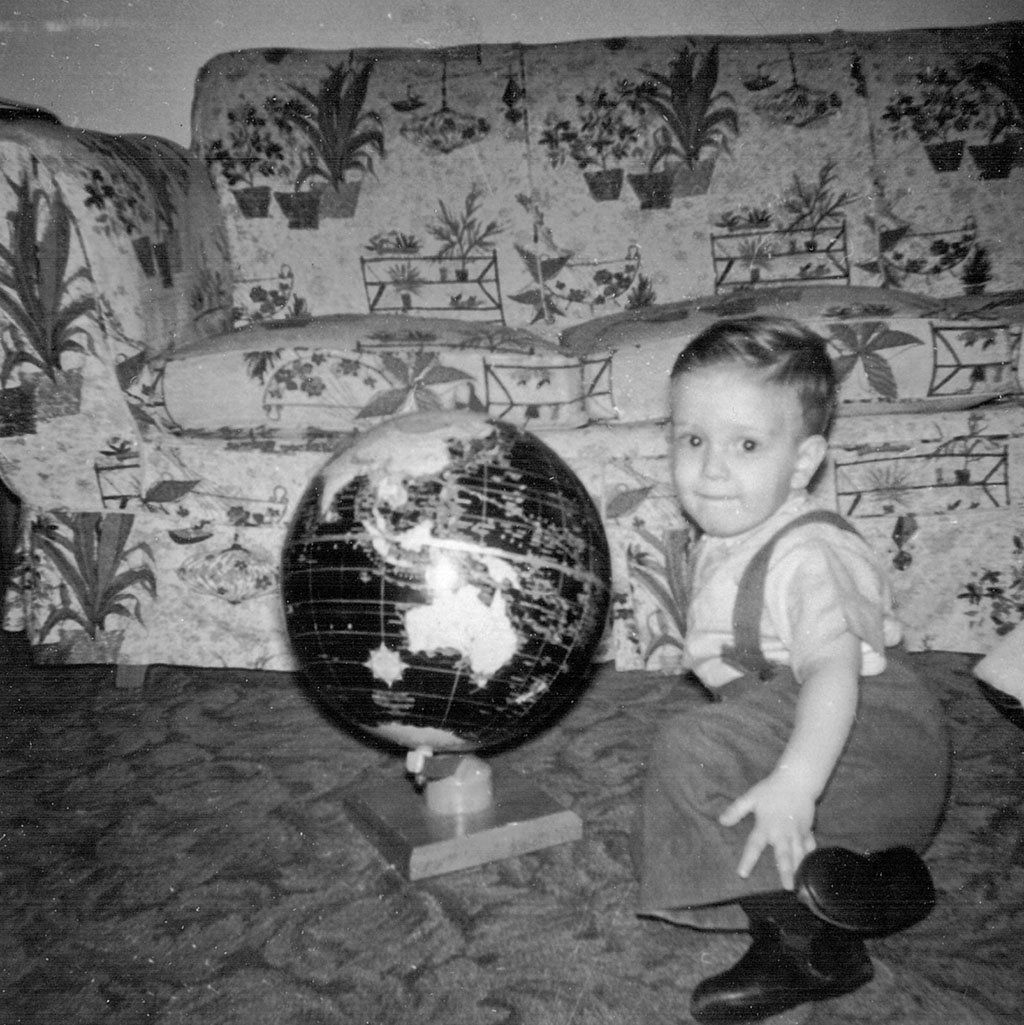

The simple truth is that I am bookish and introverted; hypnotized by objects, patterns, and minutiae; fastidious in writing; uncommonly serious, yet blessed with a keen sense of the ridiculous. I remain intensely curious about the world, as I was enticed to be from my first spins of a globe as big as I was. Here, I begin with those childhood years in the Bronx. A troubling sign of arrested development? I hope not, but I did not grow up in a professional milieu. My choices were surprising and often self-directed. It intrigues me to see how much my upbringing and early interests have colored my academic career and the topics, questions, and methods of my research and teaching. At a moment when higher education has become a dividing line and arena of cultural conflict in the United States, it may be timely to tell what the liberal arts and sciences have meant to me, even as I describe the challenges the academic life posed for a newcomer.

I turned up late in my extended family, forever the "baby", as the postwar baby boom sputtered out and more fruitful branches of our kin dispersed. Stuttering ("dragging my words") stunted my social skills as well as my speech. Of course, I couldn't talk about it, but the ever-present terror of befuddled speechlessness in a classroom, at a deli counter, or helplessly clutching a telephone (a device I still despise) lent urgency and agility to a verbal gymnastics of sounds and synonyms. Uttering any remotely suitable word would be less ridiculous than wordless ridiculousness. Pronouncing the right one quickly and effortlessly was a personal triumph to trump any triple word score in a family Scrabble game.

Conversation was seldom banter, but a battle between what I could say and wanted to, between an easy back and forth and my ill-timed interruptions blurted out when a blocked tongue loosened. Things that most needed saying were stressful to express and best left to brooding. Sheltering in silence led me too to observe intently the intricacies of interactions many may maybe ignore. No wonder that in high school, the morose introspection and existential preoccupations of Dostoyevsky's tormented characters gripped me. Discovering sociologist Erving Goffman gave me a secret friend and guide whose deceptively dry prose dissected the mundane performances of daily life, lightening the load of stigma and shame.

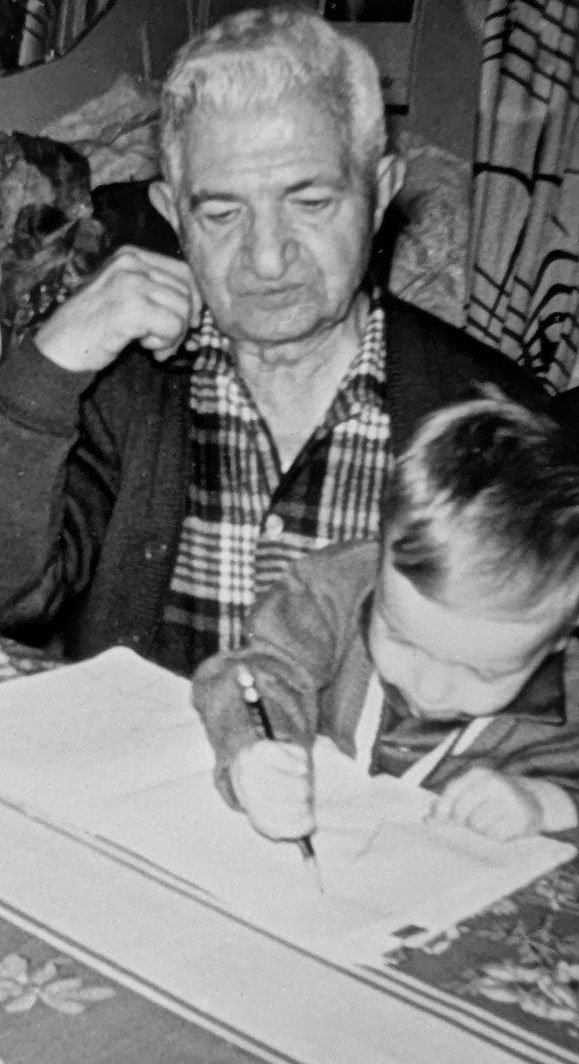

Alongside mute stuffed animals, books were my most reliable companions from the earliest age. I credit my parents for nurturing this beyond all measure, even if it was not their world. As children of immigrants, they promoted their sons' education as a ladder to success and acceptance, and a marker of family achievement. My mom had certainly taken it to heart when a teacher derided her Sicilian mother as "illiterate". With a rage that rose in every retelling, she'd proudly recall how her fiery retort had sent her to the principal, but won a promise she'd never hear that again.

Raising her toddler, her top concern was a more basic one. I was a reluctant eater (no longer!), a grave matter in an Italian-American household. Before political correctness, our family doctor railed irreverently that I looked like Mahatma Gandhi without a sheet. In desperation, my mom distracted me by teaching me how to read while slipping forkfuls of food into my mouth. Baby lamb chops passed muster: I had refined tastes. It worked (along with vitamin B12, "beef tea", chicken soup, and coffee with raw egg). I survived...and, I read.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025