As I clamored to practice my new skills, my mom hammered and raised bookcases to house evermore books. These were thick, heavy shelf-fillers: an encyclopedia and almanacs; Will and Ariel Durant's Story of Civilization; the lavishly illustrated Time-Life Ages of Man; Giant Golden Books and pocket-size Golden Nature Guides; atlases, National Geographic magazines, a children's Bible, and The Jungle Book. Reading, daydreaming, and collecting, dabbling in science and stargazing, playing with crayons or clay occupied my time. A neighbor always remembered the serious child who spoke with such big words of "gigantic" ants. Decades later, my dad put it more bluntly, telling my wife-to-be, "he was senile at the age of five."

Deploying her full force, my mom had our parish school, St Raymond's, admit me early, although my birthday fell a bit too late. My eagerness outweighed any risks. In fact, my age and meager appetite for both food and athletics would condemn me to be among the smallest boys in each class, mimicking my family role. Chalking up absences from a year of ear infections, I was banished to the back of the first-grade class because, as the teacher declared dismissively, I was never there. Exiting the building without my winter cap and ear flaps provoked my waiting mother's wrath, but I dared not say the nuns decreed that gentlemen—even the littlest ones—must not put on hats indoors. But, there were more books. My fourth-grade classroom had a young reader's version of Marco Polo's Travels. Its wonders and far horizons held me spellbound. It helped too that he was Italian or, as we'd say, "his name ends in O."

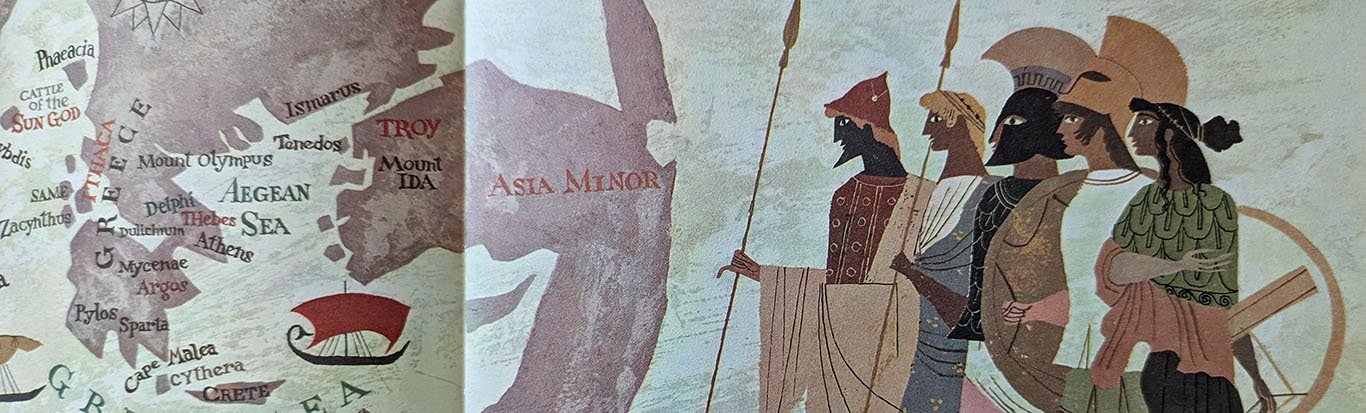

Soon, the Parkchester branch of the NY Public Library had its turn to meet my mom who swept in to insist I receive an adult card. Resistance crumbled. I devoured Harold Lamb's historical biographies with their splendor and exotic settings. And what a fearsome company they were! Genghis Khan, Tamerlane, Babur, Cyrus, Alexander, Hannibal, Theodora, Peter the Great, and, lord of all, the Ottoman sultan, Suleiman the Magnificent. In such a group, Charlemagne fell short, a harsh judgment later hardened by his outsized figure astride my field of medieval studies.

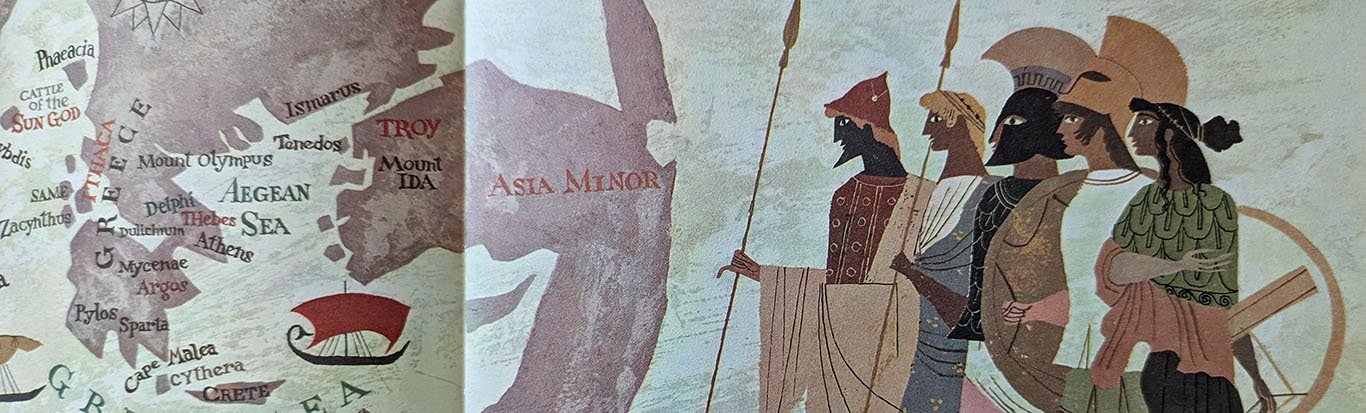

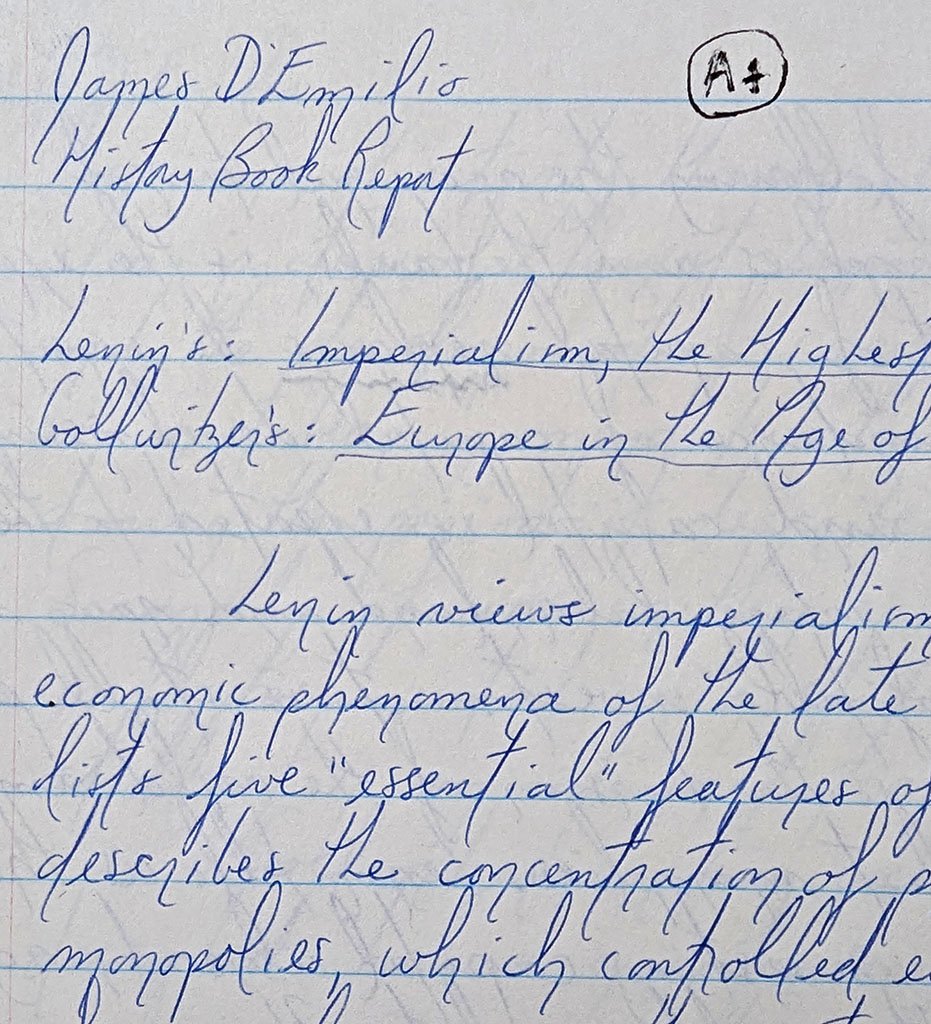

Books, words, and objects, not ball courts, birthday parties, school dances, or extracurriculars, defined my adolescence. In the wake of the cultural upheavals of the 1960s, my Jesuit and lay teachers at Regis High School valued initiative and inquiry. When a book on non-Euclidean geometry caught my eye in the school library, I read it for a tutorial. Details have dimmed, but not the startling revelation that flipping one or two simple premises could change everything. Asked for a book report on modern Europe, I thought Lenin's Imperialism just the thing. To his credit, Mr. Connelly approved it with a bemused squint, but "balanced" it with Heinz Gollwitzer's Europe in the Age of Imperialism. A half dozen of us, bonded by our oddities, implored the kind-hearted Father Fitzpatrick to lead an ad hoc "seminar" on medieval and early modern Christianity where we delved into topics of our choosing. For me, the strange allegorical readings of the Bible in Jean Danielou's From Shadows to Reality and Émile Mâle's Gothic Image unveiled a "non-Euclidean" vision of long familiar episodes.

I was disappointed that Regis's zeal for reform had done away with ancient Greek. One summer, I taught it to myself, a delightful alternative to dreadful day camps. That fall, I found a co-conspirator in Father Callahan who gladly agreed to tutor me, though my pick of Lucian's satirical Dialogues of the Dead raised an eyebrow. Bowing to my bizarre tastes but briefly, he soon shepherded me to Plato's Apology, some Homer, and Euripides' Medea, a play I sensed he craved a rare chance to teach. Greek, Latin, and German led me to translated classics from Aeschylus to Zarathustra.

By contrast, I have blotted out most of what I read in four dreary years of English classes. Part of the drill was what we now call "oral communication", a chilling phrase that suggests to me a medical procedure. The lyrical dreaminess of Look Homeward, Angel did leave a lasting impression, especially its final reverie amidst memories parading past and marble angels that strutted and fluttered by. But modern British and American literature of a realistic sort I deemed dull and wearisome, soullessly mired in material affairs. I detested the Gatsby crowd and Joad family equally. Left to myself, I roamed the eerie realms of Tolkien and C.S. Lewis. I was engrossed with the grimness of Thomas Hardy's novels, one after another, as fatal passions and fateful circumstance ensnared characters I adored.

Eclectic in their subjects, the books I fell in love with taught me to admire the beauty of the words I struggled with and to escape the familiar or routine. In a Bronx apartment, they took me to countries I knew from albums of postage stamps. I browsed illustrated books of nature and science to recognize the defining features of a seashell or the forms of constellations and clouds in the sky. I enjoyed seeking out patterns in poems and beneath the surface of stories and plots. Reading novels and plays, my lonely fretting as a stutterer alerted me to ironies and incongruities and to what appearances may hide. Furnishing ample palaces of the imagination, books carried me off to olden times and faraway places, directed my inward journeys, and explored those mysteries and elusive truths that a Catholic education trained my eyes upon.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025