With time, institutional aspirations favored graduate education and fields of study that could sustain it. Administrative fiats, hires, and raw muscle bent my department inexorably to modern and contemporary culture, theory, and...the horror, the horror...North American subjects.

Amidst pre-professional tracks and the frenzied pursuit of patents and scientific research, the generalist seemed a relic of an era as long-gone as those I studied. Even within the humanities, the role carried what academics were inclined to regard as the unpleasant whiff of the amateur. A colleague had warned me of this: the unusual scope of my teaching would hinder my research and open no doors in disciplines where I might be dismissed as an intruder without the credentials or expertise of specialists.

In the end, I was marooned...

...But wait, I spy Charon's ferry drifting towards my lonely isle. I knew he'd come at last. I sense an opportunity. Should I hitch a ride once more? A final tour of the archipelago?...

I dedicate Art History Stuff, the last of this trinity of websites, to my photographs of monuments beyond Galicia. I offer it to various audiences: travelers and anyone curious about art, culture, history, and religion; students, teachers, and other professionals who may find it helpful; and those who enjoy objects, patterns, and workmanship, as I do. Join me in looking and seeing! Together, we may explore different paths through the history of these works. I still remember Moralejo's paean to art historian Hanns Swarzenski in which he extolled the plates in Monuments of Romanesque Art as a visual conversation, a history of art without words.

For over a half century, I've eavesdropped on such chatter while inspecting and photographing monuments. Despite the chasm between my teaching and scholarship, I quietly persevered with my research. For nearly two decades after my PhD, I crisscrossed northern Spain with Ana on yearly field trips. Learning to drive did, I reluctantly admit, make this easier. Twice, I ventured to northern France and Burgundy. And, yes, it wasn't totally out of line for interviewers to bring up Chartres or Bourges. Conferences in Poitiers gave me a taste of the exuberant Romanesque of western France. Thankful for external grants and internal awards from the University of South Florida, I also scrimped for unpaid leave and always skipped the income summer teaching could have earned.

Writing, editing, and translating my book (2015) on Galicia paused this fieldwork. In 2014, a conference took me by chance to Modena. I had not been to Italy since a Courtauld Summer School in 1982. Ana joined me for part of the trip—her first to Italy. I went back to Parma, Ferrara, and Ravenna; we were among the day trippers to Venice; and we took an old-style walk to a site new to me, the abbey of Pomposa, to find the added surprise of another Italian wedding. On my last day in Milan, I caught a train before dawn for Verona where so much of it all had begun. My mother had often pleaded with me to light a candle in every church. Too late to please her perhaps, I lit one before the smiling bishop St Zeno. I've lit more since.

Everywhere I went in Italy, a flood of sensations reminded me of how much it had meant to me. How could I possibly have stayed away so long? Why?

...e volse i passi suoi per via non vera,

imagini di ben

seguendo false

che nulla promession rendono intera. (Purg.

30.130-32)

As a chapter closed, another began: I have returned eight times, up and down the peninsula from Lombardy to Puglia. With digital photography, my archive has ballooned. With effort and good fortune, it may continue to grow.

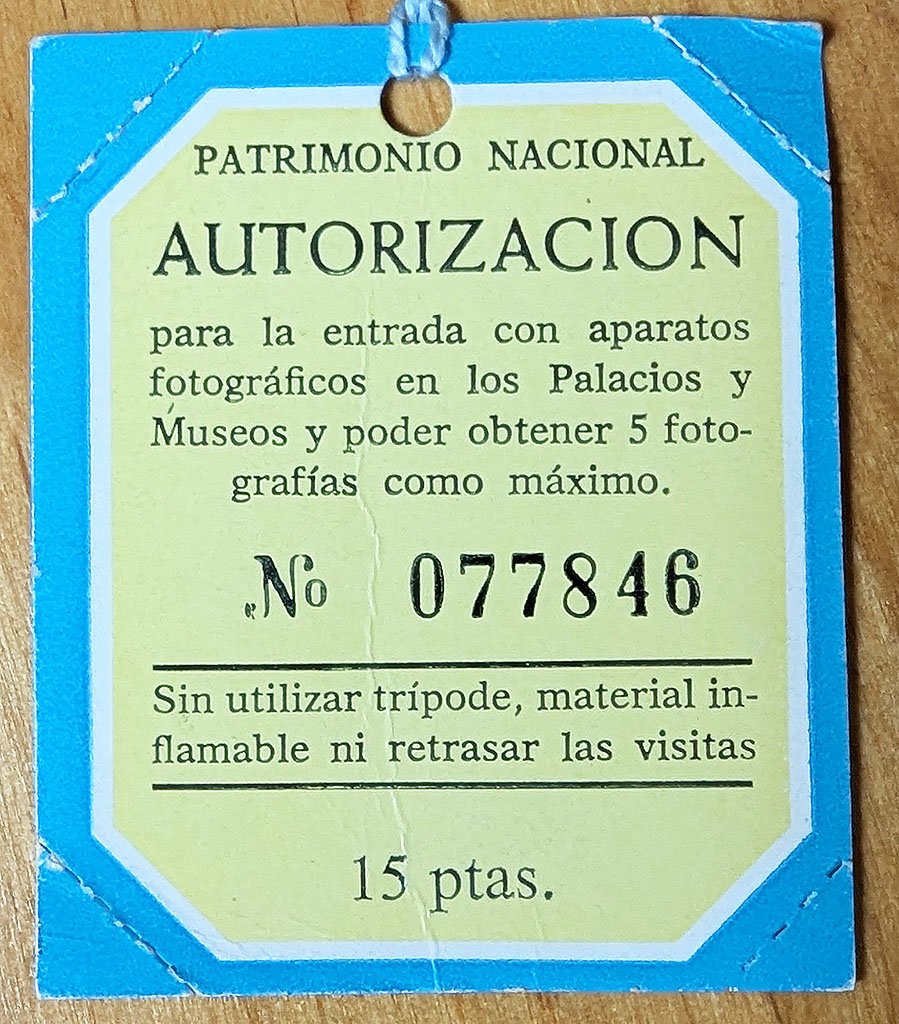

Field trips once meant a bulky tripod, jacket pockets bulging with lenses, and a shoulder sack packed with canisters of film and cameras for slides and black-and-whites. Indoors, there were long exposures on a tripod. Permission could be denied (the unwritten policy, I figured, was, "We allow photos, but not good ones"). Every shot had to count. Results came at the end. Years later, I search my slides or contact sheets in vain for that overview or detail that somehow I didn't shoot. Then, I remember...

Today, photography is easier and images a click away. The technology that makes this possible makes we wonder whether it's worth the trouble to show mine. Am I just reliving that five-year-old's delight in collecting, organizing, and displaying objects, mixing and matching them? That would be fine—but I do look forward to developing and sharing my insights into the kinds of works that first led me to art and its history, and still grab my attention: topics passed over in surveys or relegated to sidebars; works beyond the ken of English-language scholarship; cultural moments that lie out of place or out of time in our histories of art; the outliers, oddities, and one-offs, like those clownish fellows on a capital at Montefiascone whose taunting inscription berates their gawking viewers as fools.

Am I that oddity I'm trying to explain? Dedicating myself to a region once dubbed the "end of the earth" completed a personal trajectory in which I was drawn to distant lands, subjects off the beaten path, art in its forgotten contexts, and unexploited links among fields of study, all with an outsider's rebelliousness and disdain for norms. Surely, my painful sense of exclusion and isolation as a stuttering and introspective child encouraged this stance, as did my coming of age in a time when authority was questioned at every turn. Whether this led to distortion and projection, or sharpened my intuitions about what others might miss is not for me to judge.

Paradoxically, marginality is now celebrated in many quarters, even within the vise of a conformity, under many guises, that grips our world more tightly than I've ever known. We have vastly expanded our view of art to encompass visual and material culture. Art history is more fully integrated with other disciplines. With political, social, and cultural change, whole classes of art works, their makers, audiences, and concerns have won the recognition they deserve. Across the professional humanities, though, there is the ever-present risk of one orthodoxy simply replacing another, as cliques of insiders erect new barriers and hand off the well-oiled levers of power and privilege to today's cool crowd. Elites and the institutions and cultures with which they perpetuate themselves are maddeningly effective at securing their permanence and masking the machinery that does so.

I'm reaching for something more idiosyncratic and personal. Serafín Moralejo once cautioned me that one cannot write a history of chance, but I was also deeply moved by a lecture E.P. Thompson gave on the Muggletonians, a religious movement that emerged from the English Civil War. They were not, as he concluded quietly, "among history's winners." Forgotten experiments and dead ends, roads not taken and leads not followed, mysteries, mishaps, and mistakes might make a mess of the history of art, but even their smallest instances remind us hopefully of an infinity of possible futures, shattering the illusion of determinism.

As I present this material, I take on a dual task: pitching it to a wide audience and doing so with a website. Let's be clear, it's not proving easy for this old geezer to master the language of coding. It will be harder to become fluent enough to explore how this medium can open multiple itineraries, non-linear, even non-Euclidean, pathways that might recreate for you that "riotous encounter" with the past that propelled me to art history. Nonetheless, the novelty of the challenge puts me in touch again with the intrepid researcher who learned so much on the road.

I cannot promise to achieve these ambitious plans. Should I just retire quietly, giving more attention to the living, before fading away to join the dead of my own dreams? Perhaps I have failed to learn the most unmistakable lesson of my career. For an outsider, everything was a test, the harder the better. From excelling in school to winning admission to elite institutions and reeling in prestigious fellowships, one had to gird oneself at once for the next hurdle.

To be sure, professional careers set entry requirements and performance assessments for everyone. But, there is a difference, I believe, between those striving to enter and satisfy the standards of a profession where they've been told all along they belong, and those pressured to prove to that very group that they merit consideration at all. At some point, we must accept that the hardest tasks are not necessarily the best, most productive and useful, or most rewarded ones. It can make sense to know when to take the car, or to follow roads others sensibly have chosen, because they get to where you want to go, with rest stops, service stations, and companionship along the way.

But, as I leave that bewildering world, and before leaving this one, my heart suggests a simpler motive. So many people on my travels have sustained me with their appreciation and encouragement of my passionate interest in these monuments which, after all, are theirs. The monk of Subiaco who said with a laugh, "Piano, piano," as I clambered madly up the rocky path to the monastery on my first visit in 1977; the Spanish abbess who helped me climb a retable, partners in crime, to glimpse the hidden decoration she had never seen; the cathedral sacristan at Ruvo di Puglia just last October (2023) who startled me with a pat on the back, a smile, and a wave as I waited pensively for a train...all of them have kept me going, more than academic accolades and assessments.

I do owe something to all those who so generously helped a stranger on the best and the roughest of days; to the students moved, amused, maybe inspired, by my enthusiasm for these crazy subjects they may have chosen at random; to the communities of friends and acquaintances of all kinds on social media who admired a photograph, praised a thread, or shared and touched me deeply with their own insights and the experiences of kindred spirits; and above all, to those family members, old and new, who nurtured, supported, or endured this insanity of mine. If I flag and falter in this final climb to one last chapel on a hilltop, I'll remember all of you, and take another step.

And, I thank all of you for reading this. I understand how much we have to read and how long a walk can be. My mom had a favorite Sicilian curse, "May they live a hundred years". I suppose it was ironic, though the twentieth century and, now, its darker aftermath could make you wonder. I prefer another view. In college, I read Bertrand Russell's autobiography. I carried one of the three paperbacks when I met up with a high school friend, Brian, for too many pitchers at the Red Witch in the Village (I did say this was a selective bio). Some of their contents ended up rolling gently across the floor of the subway car, as I slumped ashen-faced with Russell's book at my side. Passengers discreetly sidled to the other end. The no. 6 Pelham Bay Line has seen worse.

I'm no Lord Russell, but, modestly, I share his sentiment that "I have found my life worth living, and would gladly live it again if the chance were offered me." And, to Brian, who left his life far too soon, I hope his keenest of eyes for life's absurdities would find something to smile at here.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025