The numbers of strong candidates vying for scarce openings made the grueling job search intensely competitive and debilitating for everyone, as it is today. Many faced obstacles far more daunting than mine. I am well-aware that the upper ranks of higher education remained a man's world, as the characters populating my own narrative make plain. My troubles, though, ran deeper than a Spanish topic, too few seminars, too many damn foliate capitals, or my unseemly flirtations with other disciplines. Looking back, I chuckle to think of myself stepping nervously into a hotel room for an interview. Nor was it just the stutter tension might trigger or my jittery aversion to electric shocks from a doorknob, upholstery, or handshake.

Academia had an elaborate set of social and institutional mores and rituals I was unschooled in and not at all keen to learn. Perhaps I had not read Erving Goffman attentively enough, but no analysis could replace acquired instincts and unconscious practice. Nor were there any "Teach Yourself" records for this one. What to say and not to say, to whom and when; which tastes or pastimes were expected, acceptable, or best kept under wraps; how to begin conversations and know when time was up; when to talk shop and when not to; when to push back or hold one's fire; who counted and could be counted on, who didn't, and why; how to make yourself count, trade favors, and "network"... I found it the most indecipherable of languages in the most alien of places.

At first, I saw my predicament as the legacy of my early years when stuttering had kept me from casual conversation, shyness from social life, and smallness from the camaraderie of athletics and sports. That didn't quite explain it. After all, I had fared well enough as a student. I got along and made friends, participated in academic and cultural life, initiated and organized study groups and work-in-progress seminars with energy, shared my research and supported that of others. I felt accepted, even if in a nerdy niche.

Navigating fieldwork in several countries had been especially satisfying. I had overcome many inhibitions, but that success was misleading. From my first trip to Europe, I profited from the shelter of that protective category: the foreigner or lo straniero, as a hotel clerk in Viterbo once named me in a log of guests I happened to see. In some ways, I was closer to home than I realized. Istria or Galicia were worlds away from the Bronx, but the good people who showed me around or invited me into their farmhouse for a meal had a lot in common with those I grew up among. Who knows how often a door was opened for me—literally—by someone who recognized that kinship intuitively, as they may not have for every academic? We had our codes too.

Many years passed before I fully realized that my personal tics paled before unseen barriers of class, culture, and professional identity that could make a weekend at a conference more disorienting than a trek to the furthest Galician hamlet. My high school and college were committed to preparing their talented students for bright futures, but they had also fostered non-conformity, in their own ways, at a time when it was fashionable to do so. Insiders understood, as I did not, that youthful rebelliousness was a rite of passage to be left behind when one had to get on in the world. There was an intellectual toughness and swagger about those elite schools that modeled a cocky reluctance, we'll say, to "suffer fools lightly". They didn't necessarily teach the novices who could wear that attitude well, or when to use discretion. US graduate programs might have offered a more deliberate initiation and networks of friends and faculty to ease my entry into a career, but would I have let them?

In the rarefied world of art history, I rubbed shoulders with the scions of curators and collectors. The Metropolitan Museum and Courtauld Institute introduced me to a few peers who, to me, seemed aristocrats sprung loose from a novel. Markers were more subtle in everyday academic settings, whether a committee meeting, cocktail hour, or the dreaded dinner party. The polished manners of those bred even in modest professional families were practiced effortlessly. Criteria for membership, cues, and signals passed invisibly before the untrained eye. New arrivals wandered in Limbo, as Alfred Lubrano termed that desolate no man's land in a poignant book I read decades later. Strangers in academia, our new identities estranged us from our one-time homes as well, for families and schoolmates eyed that disdainful world suspiciously. Through it all, I resisted the impostor syndrome we talk about today. I believed I deserved to belong and I refused to imagine that I was ever the one playing the Wizard of Oz.

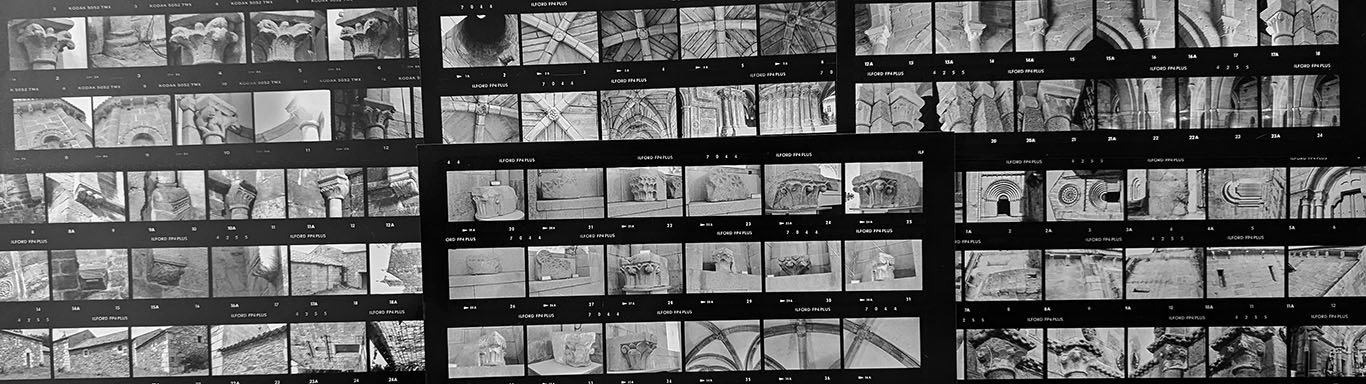

Innocently, I would peddle my wares at annual College Art Association conventions for six years, circling aimlessly from sessions and book exhibits to job centers and interviews. Looking for something? I wouldn't have known to say what it was. Before the internet and instant global communication, I was at least grateful to meet colleagues with shared interests and see them annually in this vast country. How many unsuspecting ones did I corner and ambush, flashing stacks of photographic contact sheets with barely visible obscurities!

My first break was a return to Reed for a visiting position, no coincidence in a world where connections mattered. It was followed by another at Newcomb College of Tulane University, an almost accidental hire for a last-minute opening announced at the convention. At both, I underwent a baptism of fire in lecturing and teaching, while grappling uncomfortably with a complex new social role. At last, I snagged a tenure line at the University of South Florida in 1988. I joined a Humanities department, then dedicated mainly to general education. My interdisciplinary interests and training were assets. For an older faculty in other disciplines that hadn't hired in fifteen years, neither graduate school contacts nor the risks of my research mattered much. Outside an art department, I gave the visual arts short shrift in that former age of clunky projectors, carousels, carts, and tangled cords; frantic shooting on a copystand; and dropoffs and pickups for same-day processing and my do-it-yourself slide library. No one nitpicked over what I included or did not.

Left to myself, my classes have indulged my love of antiquity, medieval Christianity, and the Mediterranean for over thirty-five years. From the Odyssey to the Qur'an, Greek pottery to Tuscan pulpits, I have roamed across boundaries and shared a wide-ranging curiosity academic silos and territoriality may suppress. My quaint approach may make today's educational bureaucrats apoplectic: I enjoy my subjects. With or without "real world applications", I believe in the relevance of our methods of inquiry for the diverse students I teach. With my unshakeable faith in the value and pleasure of learning, born from solving puzzles, perceiving patterns, and discovering relationships, I find my topics endlessly fascinating and enriching. I encourage students to embrace those challenges, and to explore past cultures, faraway places, and the magic of words and images as I have. Fending off the abominations of "learning outcomes", "deliverables", and "metrics", like so many demons babbling blasphemies, I have soldiered on, "best practices" be damned. Under darkening skies, I am made melancholy by such diabolical perversions of that divine gift of language tough love had taught me to revere.

Words and images, books, art works, monuments, and all their makers, these have been my friends and lifelong companions. Master Mateo, Giovanni Pisano, and countless others of less renown have been partners in my own dialogues with the dead. I chase their flittering shadows with vain longing, like those faintest stars I once marveled at seeing only through the corners of my eyes. Through it all, I have sought to communicate the uncanny intimacy of those encounters.

ut primum iuxta stetit agnovitque per umbras

obscuram, qualem primo qui surgere mense

aut videt aut vidisse putat per nubila lunam

Maybe I've convinced you too.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025