Our family's Catholicism was one that kept the supernatural close. It was woven into the annual calendar and weekly rhythms: Saturday confession and Sunday Mass; Lenten fasts and the Christmas crib with the stable my uncle made; the rituals of Ash Wednesday, Palm Sunday, the Stations of the Cross, and the Blessing of the Throats on St Blaise's feast. Meatless Fridays meant fish, pizza, bean soup, or, now and then, homemade parsley pie, a vestige of rural poverty turned treat. Passing by our imposing church and the tall Irish crosses of pastors' graves, I crossed myself. I whispered prayers at bedtime or not to be called on in class, and rapidly repeated the refrain for a lost object, "Jesus was lost and he was found."

Our apartment was a gallery of modern devotions: the Infant of Prague, the Sacred Heart, and a Sicilian Madonna; prayers, holy cards, and vials of Lourdes water; rosaries my parents said each day and medals they wore of the Virgin and St Christopher. When dire needs demanded prayer, my mom was the go-to specialist in trusted remedies like the nine-hour novena. Reminding her of that hourly pause in her hectic day was a duty to be taken seriously.

Beyond the rites of the modern church lay other beliefs in the shadowy fringes of orthodoxy. As a six-year-old, my mom had traveled to Sicily with her mother and grandmother in 1931. The little girl from America rode a mule to the fields with her uncle, a memory she cherished. She returned with pious tales as well. She was shown a spring and rocky hollows linked to legends of St Sofia, the town patron for whom she was named. A priest in our family tree was said to have saved villagers in a torrent, earning a local cult. In 1956, my grandmother's full recovery from a cerebral hemorrhage was the miracle that answered any doubts for her daughters (and her doctor).

Saints, miracles, and prayer defended against unseen dangers. Early on I was warned of when, how, and with whom I had to ward off the evil eye. My dad's disturbing dreams of the dead delivering cryptic messages or pleading for entry at a locked door set off hushed phone calls and anxious apprehension.

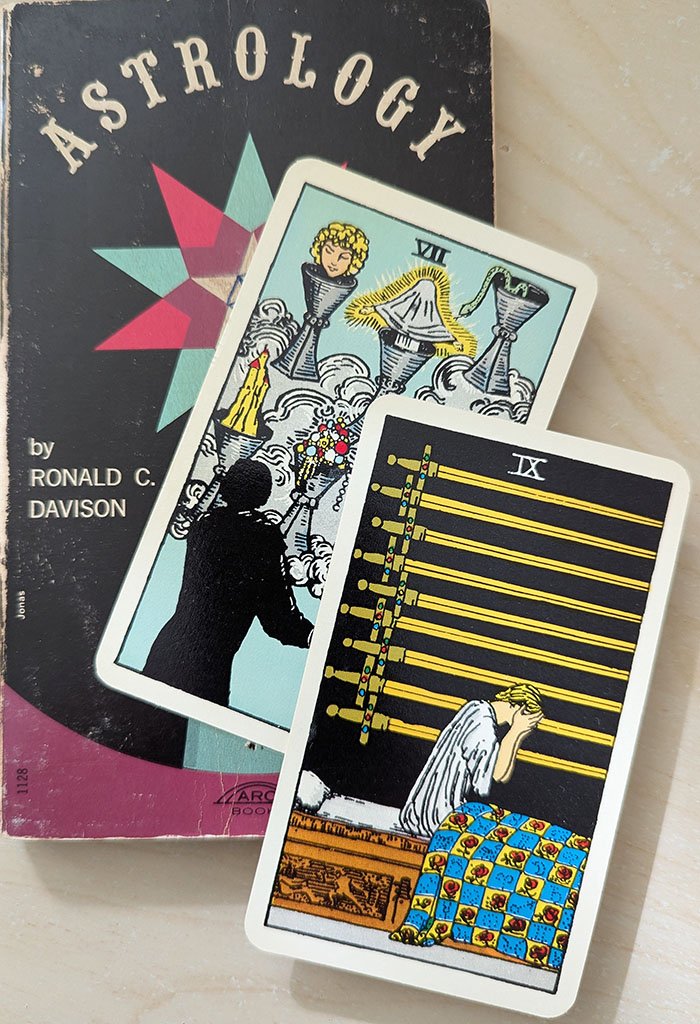

At the dawning of the age of Aquarius, this Catholic choirboy found other routes to the invisible worlds whose presence was so powerfully felt. The haunting images of the Tarot became prompts for portentous plots. As a seventh-grader, I kept busy on the snow holiday that buried Mayor Lindsay by digging into Ronald Davidson's concise introduction to astrology. Expounded methodically as a science by C.E.O. Carter, astrology suited me best. It married my fondness for numbers to a space-age fascination with stars and planets and the pleasures of piecing together a puzzle or perceiving a concealed design. More practically, casting horoscopes for my dad's co-workers earned me cash to demonstrate industry and dodge more customary (and social) teen employment.

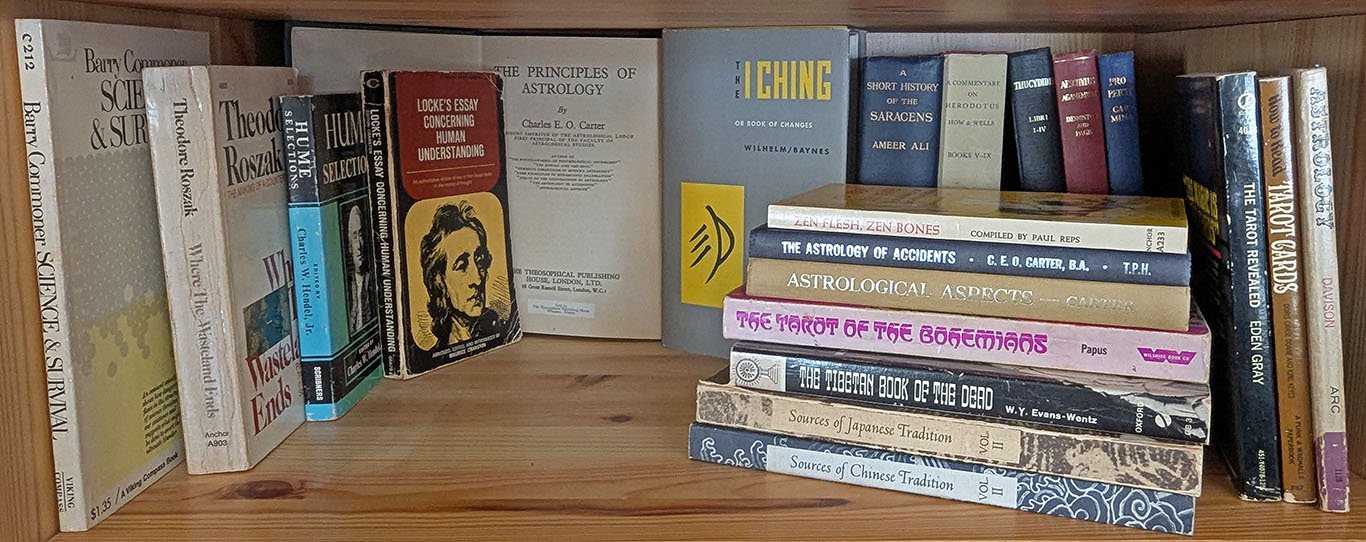

The secrets of the occult summoned me to Samuel Weiser's in Book Row on Fourth Avenue. This was the motherlode. Up and down the narrow aisles of that warren of esoterica, each section opened a magical portal to parallel worlds of enlightenment and peril. There and at nearby Strand Books, cluttered shelves and stacks piled high spirited me to Asia and the Near East too. Weiser's featured these distant continents as repositories of hoary wisdom. Prized gems were the I Ching, for which I undertook a meticulous ritual of meditative reading and divination with robe and incense, and Syed Ameer Ali's History of the Saracens with its unusually sympathetic portrayal of Islam, the Caliphate, and the achievements of Arab civilization. That perspective clashed with what I was learning of European—and Catholic—history in school. The Strand also launched a lifelong collection of Loeb Classics and Greek and Latin texts and commentaries. Grabbing whatever bargains I could get, the serendipity of less-known titles left behind by more discerning buyers slyly subverted the sanctity of any canon.

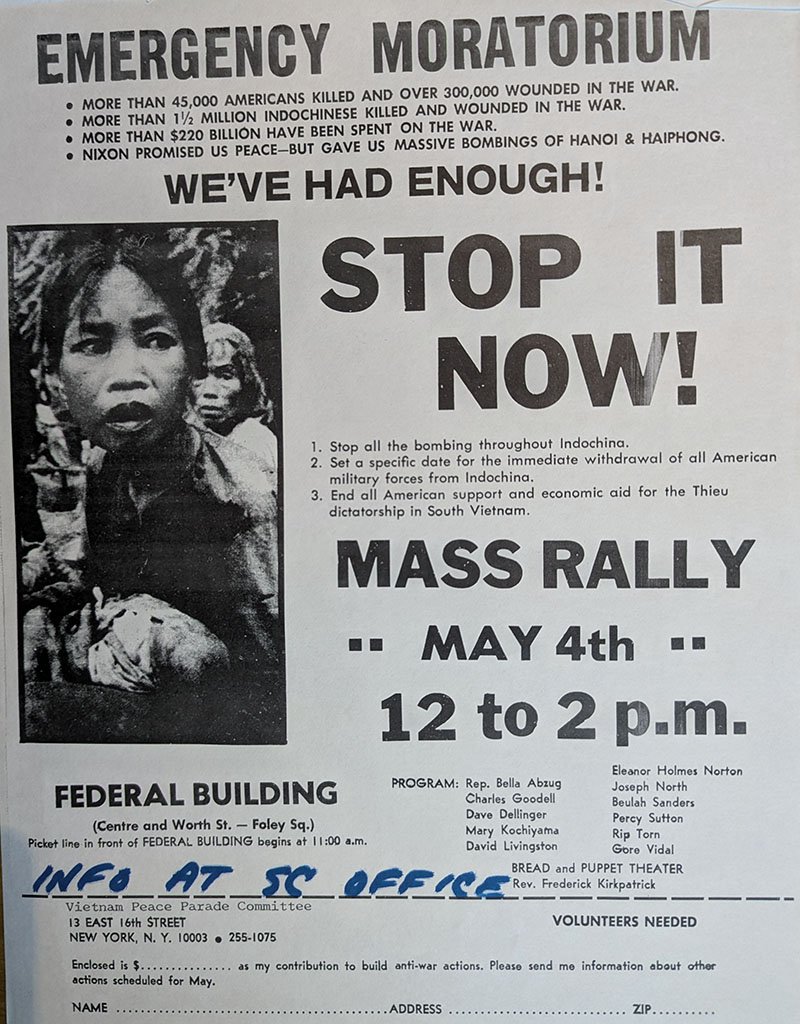

Through these years, my brother John awakened me to the politics of a world in turmoil. He fed my interests in history and culture, and blazed a trail to Regis, college, and, along the way, to Europe with the turn to art history it precipitated. My elementary school years spanned the period from Vatican II and the Civil Rights movement through the tumult of 1968 and the next year's Vietnam Moratorium Days. A handful of us more attuned to the adult world prepped to join the older cohorts of protesters the nightly news portrayed on chaotic campuses and boulevards.

For youngsters in a hurry to grow up, rebelliousness meant more than old-time pranks like splattering unfriendly storefronts with eggs on Halloween. Our aged eighth-grade teacher, whose nicotine-stained fingers repelled us, supplied a ready target for our righteousness with his racist rants. To rid himself of one student's pesky rebuttals, he exiled him to the front corner, flush against the blackboard and out of his sight. Underlining the segregation (in an all-white class), he christened the fair-haired, freckled Irish kid, "our little Negro friend". I landed in the back, this time for being too present. From far behind, I could still see Sean—and I see him now—head tilted and hand perpetually raised, silenced and unseen in unyielding protest.

Books, though, remained my passion. John's texts from Columbia University's core curriculum stocked our shelves with classics of European literature and philosophy, and of Asian religions and cultures I was keen to explore. Rummaging through this trove, I was so taken by Locke's Essay Concerning Human Understanding that the cover portrait inspired me to paint a ghastly canvas for Hilda O'Connell's art class—surely the sober philosopher's sole stint as teen idol. Despite this unpromising trial, it was art, not philosophy, that was about to take charge of my future.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025