Books—and their covers—were one pathway to art and much else, but I also loved objects, puzzles, and patterns; the shapes of small things, their colors and fine details. Counting, classifying, and arranging them all was serious business. I collected stuff, anything really: stamps and coins, baseball cards and Kennedy cards, rocks and shells, even a butterfly I netted alive whose pointless agony I have never forgotten. Some of this was just hoarding, as a glance at any space I quickly fill—or my bottomless email inbox—can confirm. But, it was also a child mastering a miniature realm to make sense of the boundless and unruly world before him.

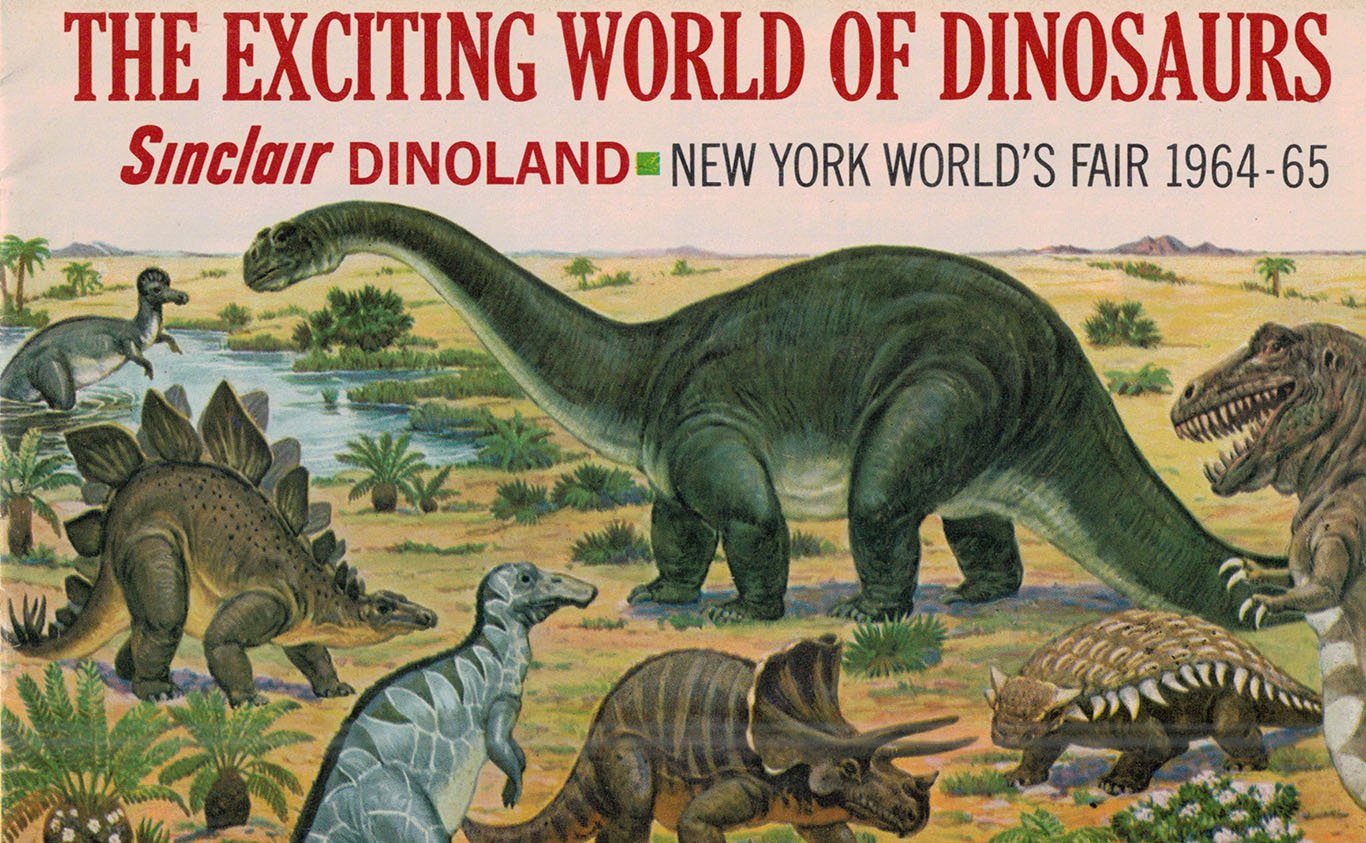

The Space Age instilled a simple faith in science that the acrid fumes of our incinerators and the fallout shelters in our hallways could not dispel. I was lucky to live in a city where the American Museum of Natural History, the Hayden Planetarium and, in our maligned borough, the Bronx Zoo and New York Botanical Garden let its residents explore every habitat and voyage to the moon and planets. For us New Yorkers, our city was the capital of the world as well. (You know that of course.) We had the United Nations and hosted a World's Fair in 1964-5. Our last in 1939, as my parents remembered, had been less opportune. Now, new countries arose every day from the wreckage of empires. The Statue of Liberty reminded us that immigrants, like my grandparents, had flocked here from everywhere. Our lively streets and neighborhoods, with all their color, sound, and pungent smells of cooking, made clear that many went no further. Why would they? That much, at least, was a pride we shared.

At the height of the Cold War, a child could not be insulated for long from frightening bulletins and headlines. In a Catholic and staunchly anti-Communist household, Castro, Mao, and the gruff, if grandfatherly, Khrushchev were a trio of bogey-men who, I feared, any billowing curtain might conceal. A decade that began with crises in the Congo, Berlin, and Cuba was ending with the Cultural Revolution in China and carnage in Southeast Asia and the Middle East. Diplomacy at the UN, protests in the streets, and a mosaic of ethnic communities made every coup and conflict resonate in New York.

Collecting things gave me little pieces of this world and tools to comprehend it. Full of history and culture, postage stamps were snapshots of one-time colonies and hopes that independence brought, of Cold War rivalries played out with orbiting satellites and Olympic medals, of folklore and customs, monuments and natural wonders. Colorful scallop shells or the glinting crystals and rainbow flecks of a chunk of granite stood in for the tide pools and rocky wildernesses I saw in books or dioramas. The Edmund Scientific Catalog was a wonder to page through. It advertised instruments to extend my vision and samples of fossils or minerals from around the globe. I was glad Santa Claus liked it too.

Collections required study, organization, and design. Albums for coins or stamps were all set to be filled, but shells had to be identified, labeled, and laid out neatly, with an eye to colors, shapes, and sizes. With my mom's help, I mounted them in carefully matched boxes: scallops, almost flat, fit in those for nylon stockings; cockles or moon shells needed roomier shirt boxes; for rocks, shoe boxes would do. What I couldn't collect, I tracked and tallied: the license plates of the fifty states or the ups and downs in the charts of songs and bands in the era of the Beatles and Beach Boys. Through urban glare, haze, and sooty windows, I sought out bits of sky between buildings and trees to trace the movements of planets and, over the seasons, constellations.

One common denominator was a pleasure in noticing details and patterns. What made a shell or leaf one type and not another? How could I tell where a stamp was from or distinguish unknown languages? I did not get rich from the time spent pondering whether the latest 1960 penny might have the less common "small date", but I did sharpen my skills. To no one's surprise, I became near-sighted very early. I learned, though, that seeing was more than acing an eye chart. For these hobbies, it meant knowledge and discrimination. The most obvious contrasts might not matter at all, while subtle details could be decisive.

I relished the visual puzzles in Highlights magazines. In some, I had to find hidden figures, a toad or rabbit sketched in the branches of a tree. In others, I had to distinguish two nearly identical drawings by spotting an extra line, an unobtrusive object, or one more flower or feather. The crowded scenes in "What's Wrong?" were a visual Twilight Zone of bizarre or creepy intrusions into the picture my mind expected me to see; it was an early lesson in transgression and the ways rules are most brightly visible when they are broken. Those challenges made me look forward to visiting the dentist. We climbed the steep and narrow staircase to Dr. Ozick's office where his waiting room had a child-sized table and stools and plenty of those magazines. My mom scheduled her appointments with mine, giving me more time for studious play.

More perversely, my glee carried over to the dentist's chair. No needles were needed. Pain was numbed as Dr. Ozick drew out the compelling drama of bible stories. I never tired of the favorites in his playlist: Abraham haggling with God over Sodom and Gomorrah; Pharaoh's stubbornness and the plagues of Egypt; Moses enduring the murmurings of the Israelites; and the bleak misfortunes of Job. His vivid descriptions of Job's camels and herds seized my imagination, even if I didn't think he got a fair shake. The weightier dilemmas of suffering, trust, and divine justice were over the head of a schoolboy, but the stories were told to be remembered. Dr. Ozick spoke the parts with comically exaggerated impressions of hesitation, impatience, and complaint, and the bare essentials to stage a scene before your eyes.

Above all, Abraham's unflinching plea to God stood out. I knew him from Catholic readings of the Sacrifice of Isaac. Whatever its profound import, a father's submissive willingness to slay his much-loved son had not endeared him to this boy. This was different. It began tentatively. They could have been bargaining over a belt in a marketplace, as Dr. Ozick characterized it. But, the suspense grew with the drumbeat of each appeal, as Abraham dared to persist, questioning with conviction this formidable God who could zap him in an instant. It was the right story for the moment: everywhere one looked, people were rising up, realizing their strength, confronting the powerful, and calling for justice. And, it suggested that twenty or ten people, perhaps even one, could make a difference.

These performances taught another kind of lesson as well. The back and forth of a repetitive dialogue anchored every tale Dr. Ozick told. Bit by bit, each round ratcheted up the tension. I readied myself for small variations or a surprising twist with the same keenness I had applied to visual puzzles minutes earlier. Like the melodies I was beginning to play on a piano, each episode had its crescendo of repetition, and its changing pace with expectant pauses and points of emphasis. As if in the expert song of some ancient bard, the rhythms and cadences that Dr. Ozick captured so well infused these stories with meanings deadened by the humdrum drone of readings at Sunday Mass. What a story meant was bound up with how it was written, structured, and told.

Hearing, finding, and seeing patterns, organizing and displaying collections, and looking through the eyepiece of a child's microscope or telescope were preparing me to put the world in the frame of a photograph. My dad worked, as a bookkeeper, for photographic firms, first Peerless Camera Store, then Berkey Photo. Discounts on equipment, film, and processing made it less of a luxury for us. He had a 16mm movie camera, blinding lights for indoor family gatherings, a projector with its unwieldy reels, and a rickety movie screen. With no fanfare or fuss, he was the family photographer. We watched home movies and thumbed through envelopes of new Kodak prints. Family members weren't shy about what they liked and didn't.

No formal lessons were needed. My technical knowledge remains minimal. Now and then, I google SLR to remind myself what exactly that is. But, I was learning about design, light, and color, what to include, and what to leave out. When I could, I took my time to size up the light and shadows, find the right angle and distance, line things up, frame my shot, and check the borders and corners, obeying instinctively the maxim my mom always loved, "Anything worth doing is worth doing well." Soon I would discover the best trick of all: choosing subjects crafted by artists who must have had a mother like mine.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025