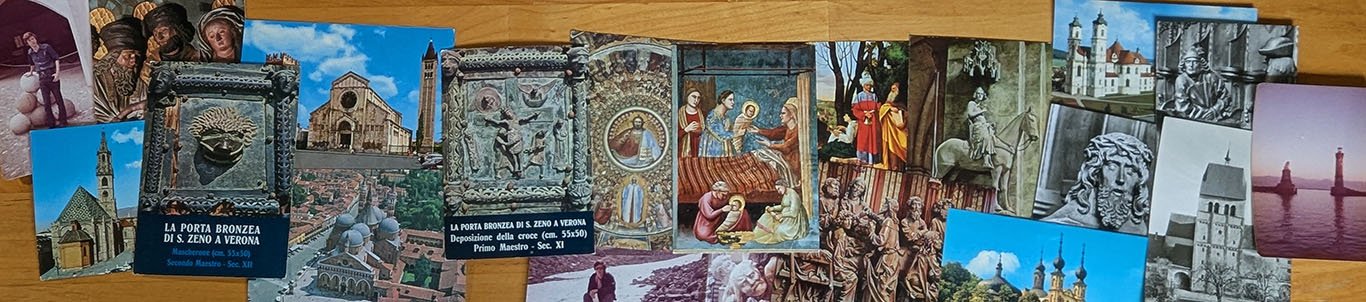

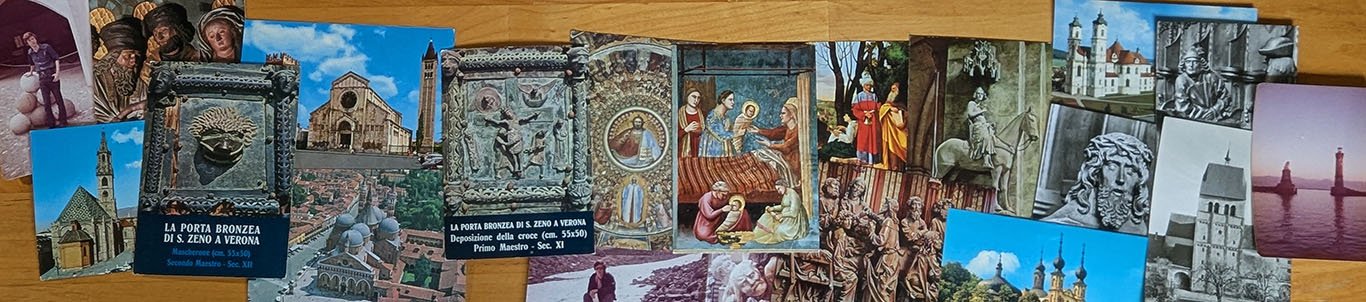

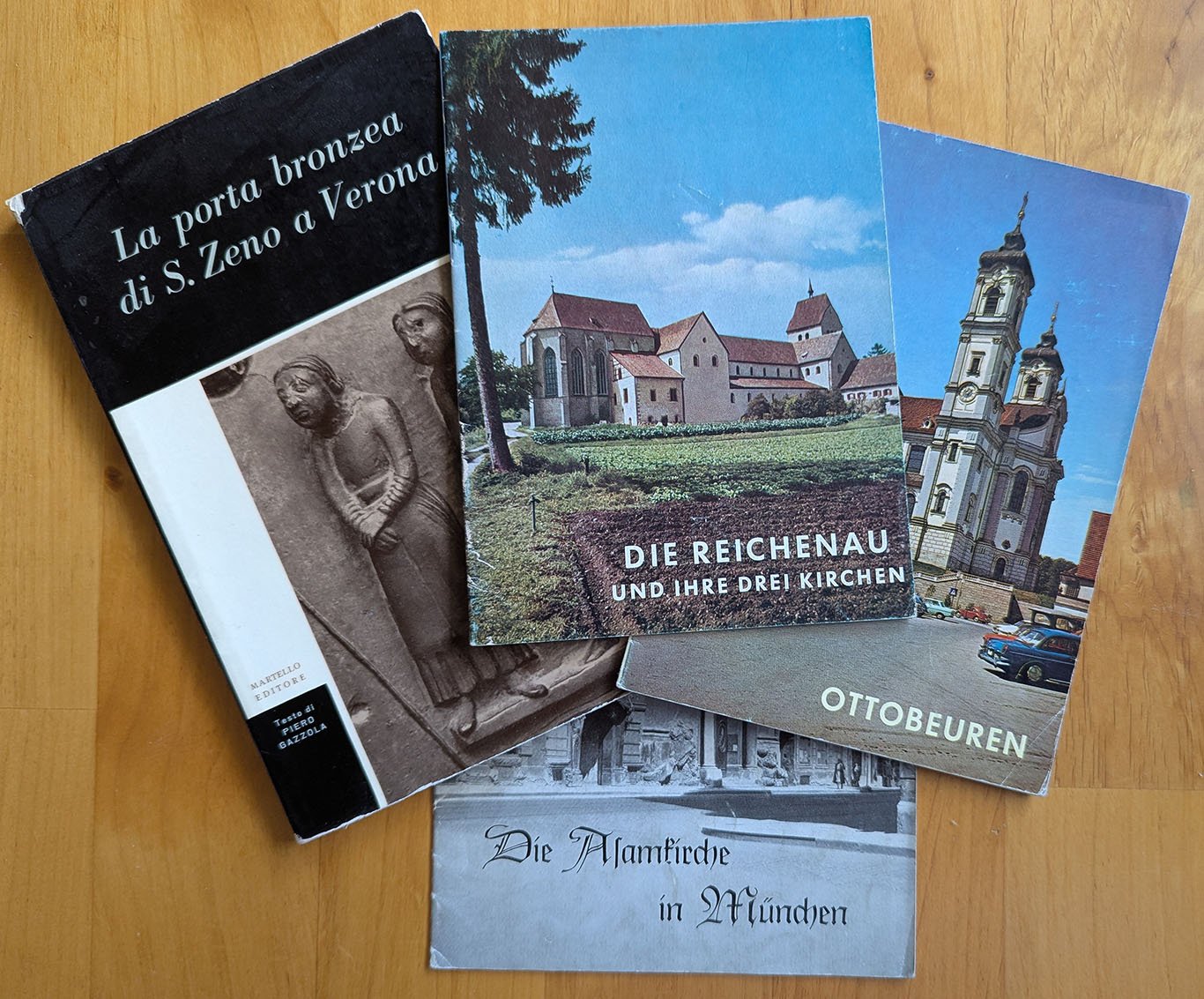

Before I started high school, my brother came back from two summer trips to Europe with stories, snapshots, and postcards. Best of all was the haul of splashy "Forma e Colore" albums with huge glossy photos of glories of Italian art. Michelangelo's Medici tombs and Brunelleschi's colossal dome were big sellers, but others remain by my desk: Wiligelmo at Modena, Antelami at Parma, Giovanni Pisano in Pistoia. To me, these artists stood as giants in places of legend. With soft syllables and vowels, their names rolled easily off the tongue like those of distant cousins. At John's initiative, books like Otto Demus' Byzantine Art and the West or Michael Ayrton's Giovanni Pisano edged out trendier teen picks under the Christmas tree.

Regis offered one summer program overseas: a month in Innsbruck taking language classes and living with a family and other foreign students, then two weeks of travel in Germany and Austria. Set on that goal, I opted to study German. Our teacher, Father Daley, had conceived the program and led it each year for a decade. In 1973, he didn't accompany us, but talked it up, before and after our adventure. I can't forget a conversation, in which he laughingly interrupted my rambling reminiscences. Staring intently, he shouted, "You're back, you're back," as if shaking me out of a dream from which, in fact, I never awoke.

Travel abroad proved supremely liberating. My outward excitement masked my nagging fears that the constraints of barely a year of high school German might shackle me as a stutterer. The opposite occurred: the confusion of tongues became a state of grace. I was a foreigner: to mix, miss, or make a mess of words was normal; effort was appreciated; hesitation elicited encouragement; warm smiles replaced mocking snickers. This dispensation was applied most liberally: travelers were exempt from mystifying rules of social interaction I had never mastered. Oddness was excused, even expected. My failure at times to conform to stereotypes of the US tourist or student seemed itself a welcome surprise to people I met.

Immersion in a foreign language engaged me, but art and monuments left an indelible mark. The first European church I stepped into was the Asamkirche in Munich, a Rococo jewel and overwhelming total experience of painting, sculpture, and architecture. Hemmed in between buildings of its height, the rippling curves of the narrow façade could scarcely prepare a newcomer for the explosive exuberance beyond the door. I would not have known then that the Asam brothers had built it as their private church with no patron to defer to. I'm grateful, though, that an artists' church introduced me to Europe's monuments.

Our excursions took us from the over-the-top Rococo ecstasies of the Wieskirche and Ottobeuren to the long-faced saints of Tilman Riemenschneider and late Gothic contemporaries. As one scorching and exhausting day dragged on endlessly, I coaxed Mr. Kaestner to divert the coach, skipping the refreshing gardens of Mainau for the monastic isle of Reichenau. Under a blistering sun, still more churches, small and severe, nearly provoked my exasperated buddies to a mutiny. My trip and story might well have ended then and there at the bottom of the Bodensee.

Short getaways to Italy sealed my fate: a day in Bozen/Bolzano, a weekend with a few fellow students in Verona, finally a return, characteristically alone, to Verona and Padua. Soaring towers and tile roofs; a rainbow of plastered walls in pastel hues, pinkish or creamy yellow stone, and deep red brick; San Zeno's façade and bronze doors bathed in blazing sun; the massive Roman arena casually presiding over the bustle of its grand piazza; ancient bridges arching over a sinuous river that bends and turns for a better look at its glorious city: Verona, I knew at once, had to be the most beautiful city on earth.

Art was down every street and around every corner: the number, variety, and scale of churches, palazzi, and antiquities were staggering. Spacious medieval basilicas abounded with painting and sculpture, marble altars, modest tombs, and magnificent memorials of every era. This art appealed to me in multiple ways: its beauty and the skill of its makers; its own history and the history it revealed; its capacity to arouse devotion and communicate ideas; and the infinitely varied patterns of its vocabulary of forms, like the sounds, words, and structures of the languages I was learning to use. Teaching the visual arts from a page or screen, I've struggled to bring together responses that tug in such different directions.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025