I knew enough of art to make my pilgrimage to Padua to pay homage to Giotto in the Scrovegni Chapel, but I had taken no survey of art history (and never did in college). This riotous encounter with all manner of monuments would start my career from different premises. I met art in places not timelines. In an intimate chapel, images centuries apart whispered together or vied for a visitor's eye. Context mattered, and contexts varied and changed. Within buildings, every viewpoint and shade of light opened new perspectives. Scenes stood within narratives laid out around them, but we also brought our own memories of these stories and of other images. Passing tourists and pious worshipers alike conjured art to life. Seen and recollected, added to and altered, framed through a camera, art from a long-ago past had a thousand lives.

What I saw was no hit parade either, picked out, lined up, labeled, and showcased, one by one, in a museum or pages of a textbook. Instead, I lingered over fragments of faces and unfamiliar stories unfolding in patchy cycles of faded frescoes, tantalizing remnants of all we have lost. Intricate designs and deft artistry fixed my gaze on a wonderland of decoration, often overlooked, where fantastic beasts lurked in lush forests of foliage. Alongside famous works, this vast supporting cast made me scorn that high society of universally acclaimed masterpieces whose luster dulled with every reproduction. What about all this other stuff!!

Beneath my awestruck curiosity, themes began to stir in my mind: the importance of place and contexts, the elusiveness and instability of meanings, the mournful sense of loss and incompleteness, the underlying structures and rules of elaborate programs and commonplace repertories of ornament, the historical layers of art and its reception throughout a vigorous afterlife, the conferral of privilege on a few, and the consignment of many to oblivion. These would slowly come into focus in college and afterwards during over a year of European travel with a Thomas J. Watson Fellowship, but some plain truths a youngster could grasp immediately. Here was more than books could contain. Far more was forever gone. Pictures on a page failed to capture the scale and contexts of art and how we perceive it. One-dimensional aesthetic judgments, schematic classifications by period or style, and celebrated benchmarks of artistic evolution brushed aside or pigeon-holed an immense heritage.

The time had not yet come when more inclusive definitions of visual and material culture would give greater attention to the subtleties of visual languages as modes of communication and the value of modest artifacts as historical documents. Later I would wonder whether our adulation of towering geniuses narrowed even our aesthetic appreciation of their own masterpieces and originality. I smiled with complicity at the resourcefulness of less-heralded artists. Shrewdly managing their constraints, they bent rules, manipulated conventions, and produced works of surprising ingenuity. I learned to respect both the resilience and malleability of traditions. This full range of art brought us nearer to the public of a bygone era. We could better understand their visual culture, if we saw it through the eyes of the most perceptive and well-informed audience: contemporary craftsmen who responded with their own creations.

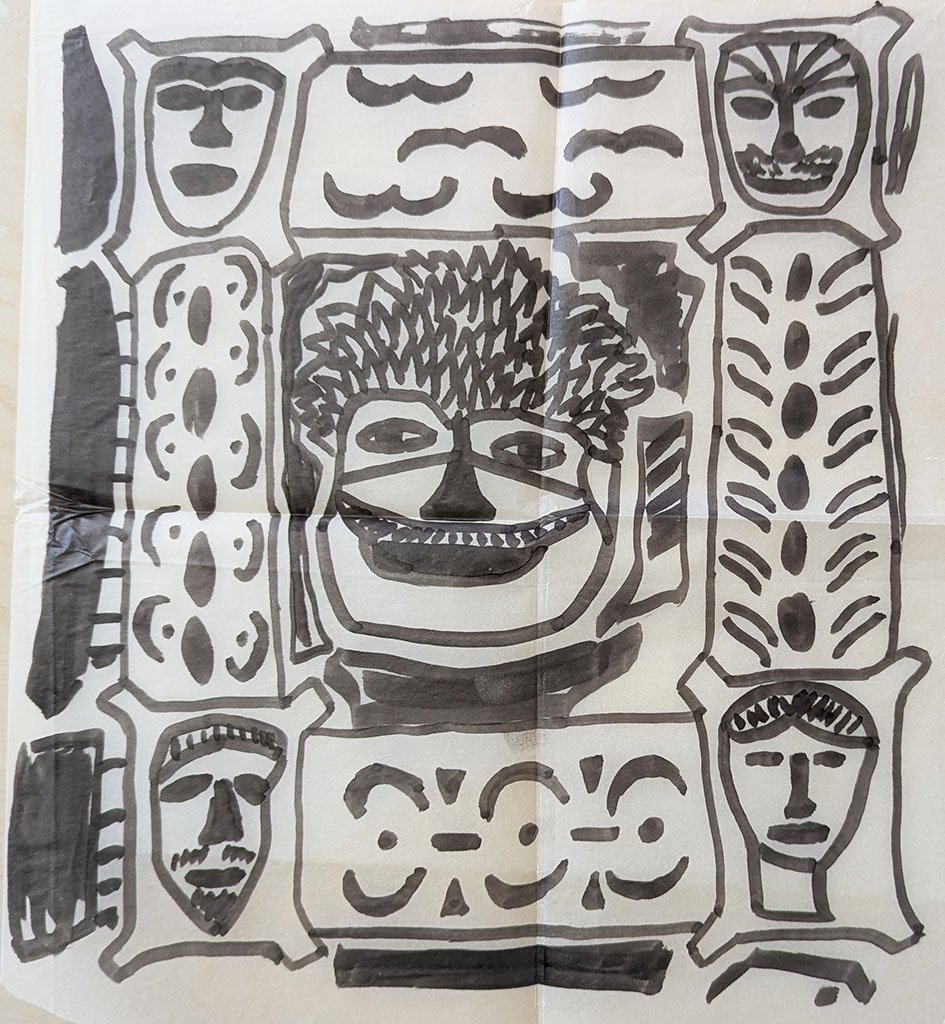

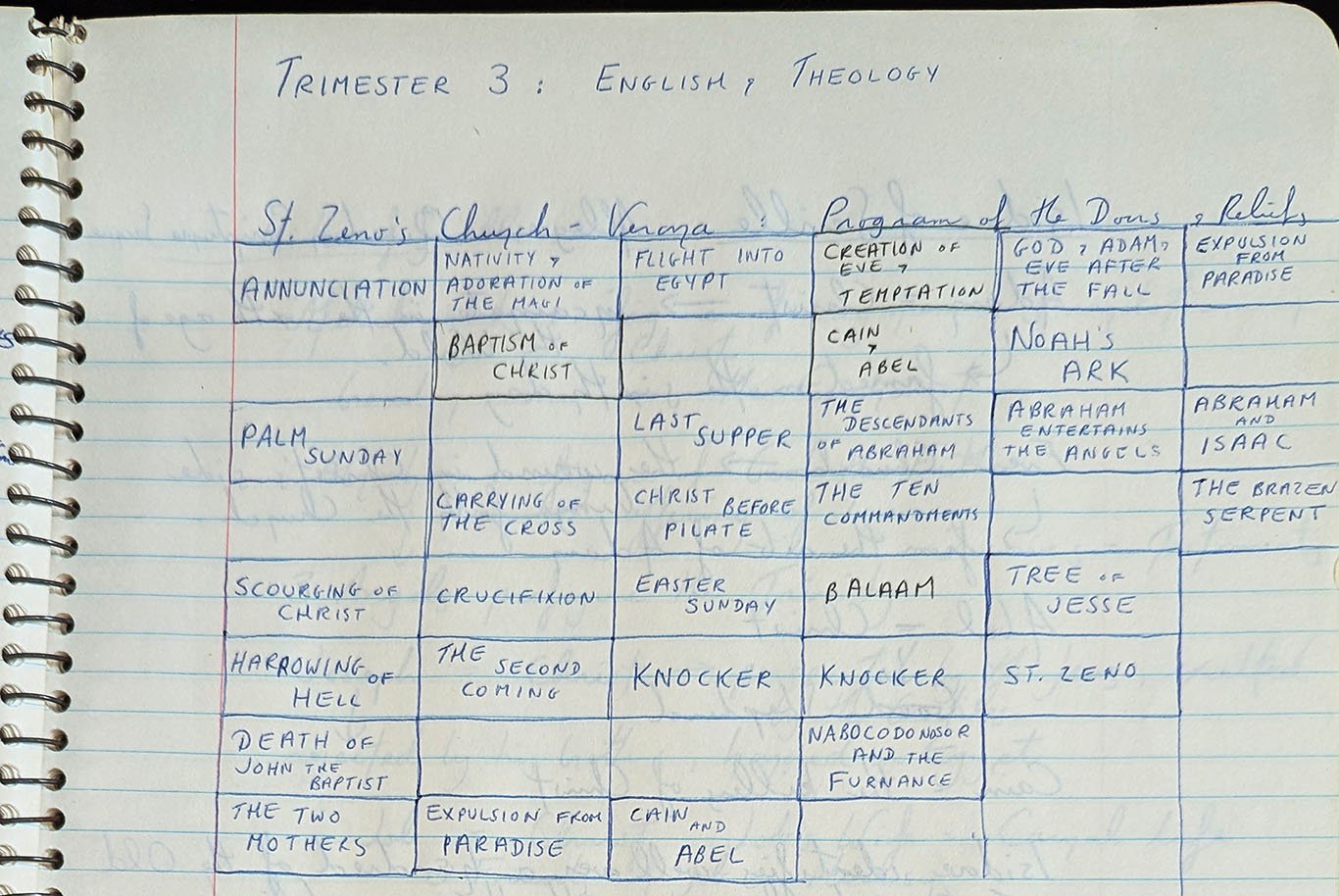

Insights like these lay in the future, but they were born from my astonishment, at the outset, that sites I admired most had missed the cut. To an American teenager, stunned by the shock of the old, Giusto de' Menabuoi's frescoes in the Padua Baptistery and the twelfth-century bronze doors of San Zeno's in Verona looked pretty good (as they are!). My obsession with those doors became something of a family joke. It took a dark turn when I slit open my thumb carving one of their panels in wood in Ms O'Connell's art class. Advancing from painting to sculpture, I engraved the memory of the doors in my flesh with several stitches and a permanent scar.

More traditional approaches to these works were hardly more fruitful. I had come home to find them left out of handbooks and, as far as I could tell, bypassed in English-language literature. How could this be? I had so delighted in the saints filling the dome of that baptistery and the luxurious abundance of the frescoes covering every inch of its walls. With sophisticated artistry, ensembles like these expounded religious teachings with scores of biblical episodes from Genesis to the Apocalypse. I searched and stretched my language skills. Near Regis, I frequented the library of the Goethe-Institut where I paged through (and pretended to read) hefty volumes packed with plates. Peeking gingerly into imported art books at Rizzoli's in midtown, I pored over pictures. The NY Public Library graciously waived restrictions to admit this earnest high schooler to the Art and Architecture Collection of its Research Division.

Entire media, periods, and regions were excised from finely distilled master narratives and categories of art history. The dazzling Rococo style of Catholic pilgrimage basilicas and monasteries of Bavaria and the Danube was a dead-end detour off the ride to enlightenment and romanticism. Giusto de' Menabuoi could commiserate with two lost generations of prolific Italian artists, as narratives vaulted from Giotto and a few contemporaries to the Renaissance and zoomed in on Florence. Coming upon Millard Meiss' Painting in Florence and Siena after the Black Death, I found it a revelation, making clear that our storylines are selective and retrospective, not predetermined. His arguments would undergo wholesale revision, but he had helped rehabilitate the precious frescoes and golden panels that appealed to me so powerfully.

Years later, I was starting graduate school when Michael Baxandall's book, The Limewood Sculptors of Renaissance Germany, featured artists like Riemenschneider and Michael Pacher. H. W. Janson, author of a leading textbook, praised its treatment of "this neglected but important chapter in the history of art." Ernst Gombrich published The Sense of Order then as well. I was entranced by its serious treatment of the kaleidoscopes, snowflakes, and puzzles of my childhood, and of the finely wrought ornament of borders and frames, architectural elements and decorative arts, that had competed for my attention at so many sites. Over the years and through thousands of photos of column capitals, carved arches, and friezes, I have fondly kept in mind his apt tribute to Alois Riegl's "masterpiece...in which the history of the acanthus scroll is turned into an epic of vast dimensions."

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025