As I was finishing high school, Reed College's reputation for academic intensity and quirky eccentricity hooked me. Both proved true. Oregon and the dramatic landscapes and coast of the Pacific Northwest had the added allure of a far-off place. An early exodus of relatives to the southern California dreamland had enshrined the American West in our family lore. Two childhood vacations had shown me its grandeur: stately palms and sun-drenched cacti, the Grand Canyon's incomprehensible scale, stark expanses of desert, black skies blazoned with the Milky Way and lit by bursts of shooting stars. Cross-country bus trips and midnight rest stops would translate its distances into more prosaic terms.

At Reed, I designed my own interdisciplinary Medieval Studies major, centered on Christian culture, religious movements, and the legacy of antiquity. Continuing my study of Greek and Latin, I partnered with Classics majors to lobby for a medieval Latin course. The anthologies we used presented their texts in ways that troubled me. Selections spanned a thousand years of medieval Latin across regions and registers, genres and authors (with the further complications, I would understand later, of scribal transmission and modern editing). Yet, the norms of the literary Latin of a thin slice of antiquity were regularly trotted out to judge some usage or construction as a deviation. It seemed akin to the ways an art historical canon set standards and assigned works to categories, when they might be appraised quite differently against criteria more relevant to their makers and audiences.

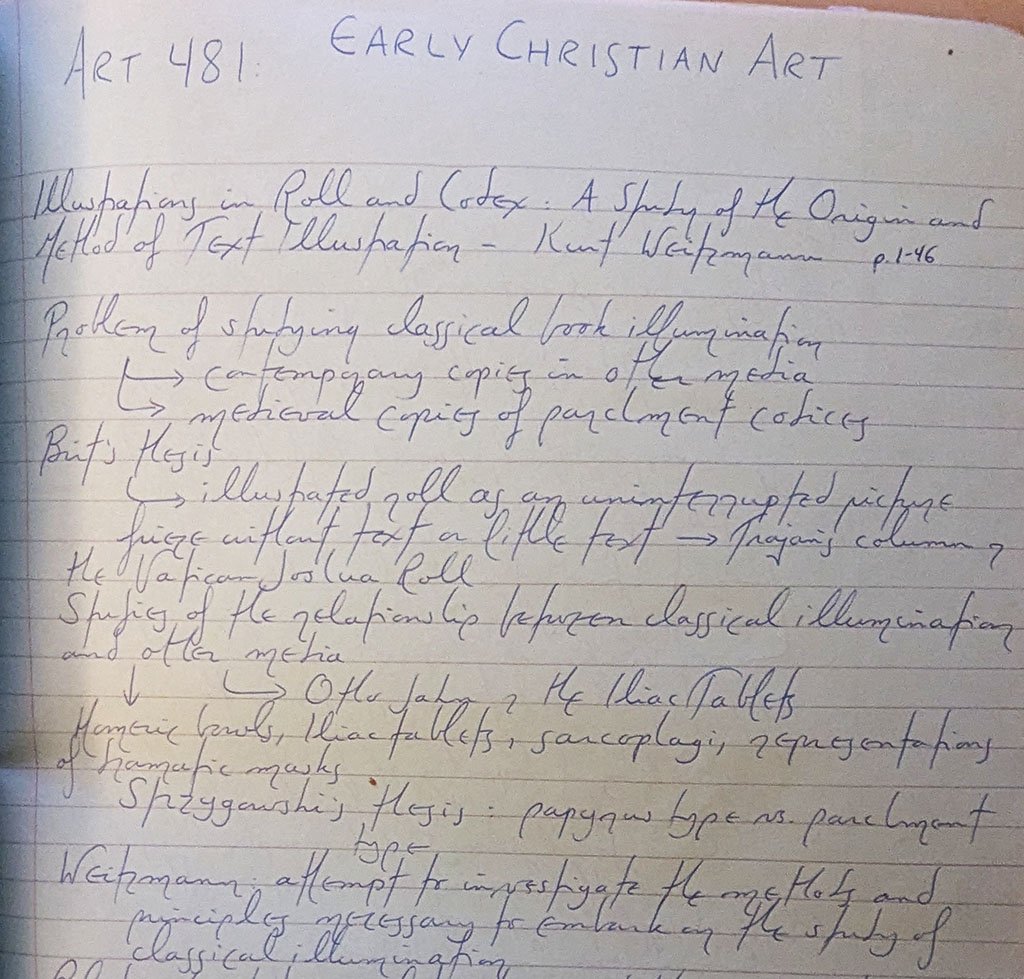

Despite the impact of European travel and a fine and supportive teacher, Peter Parshall, I had remained leery of art history and these haughty canons. The discipline's elite pedigree and ties to the contemporary art world were ill-fitted, I thought, to the sacred art and historical concerns that engaged me. In a tutorial, Peter guided me through the work of Kurt Weitzmann and a growing cadre of disciples who were shaping American studies of medieval book illumination and iconography. His method of reconstructing prototypes and examining the copying process attracted me for its analogies to the textual studies of that era, its effort to recover a lost past, and its careful identification and interpretation of minute variations.

These rigorous exercises taught vital skills. Over time, though, my engagement with provincial art, often dismissed as derivative, persuaded me of the arguments of critics of his premises and methods. Works we have were too often reduced to tools for re-creating nobler ancestors. Rigid analysis of models and so-called copies risked turning the latter into mechanical products, while overlooking their value as creative responses to predecessors and contemporaries. At its most extreme, this diminished the agency of artists who were more than error-prone imitators or mindless makers of pastiches. Rather than bringing lost heritage to light, as I hoped, it lessened and distorted the significance of art that did survive and of the contexts for which it was made.

In the end, my interests in deviance and defiance, how rules are made and imposed, and why some innovators are canonized, others condemned, steered me toward my BA thesis on eleventh- and twelfth-century heresies. Aiming to go beyond the history of ideas, I applied models from my anthropology classes and plunged into the work of the East German Marxist historians Ernst Werner and Bernhard Töpfer. I completed my BA in three years, not four, thanks to Advanced Placement credits from high school. This was a well-deserved boon for my parents who were footing the bill for my uncertain goals. I had no regrets, but it meant one less year of socialization into the academic profession. I doubt that would have mattered.

Upon graduation, I was feted with an enviable buffet of awards for United States PhD programs in History or Medieval Studies or a year or two of study in England or West Germany. I accepted the Watson Fellowship instead. Its unstructured year of travel arrived as a blessing from heaven. Mine was to be devoted to medieval saints' cults in southern Europe. With frugality, single-mindedness, and an ascetic indifference to food, I would stretch that wad of travelers' checks for sixteen months and straggle back barely weighing one hundred pounds.

Next to this Wanderjahr, other options were inconceivable: who on earth could refuse it? It saddened me that a couple of professors I held in high regard voiced strong reservations. I had no idea of the web of favors and calculations that academic recommendations to prestigious powerhouses might involve, or of the networks deemed essential to a career. Worse still, I casually commented on these misgivings, in a general way, to Watson representatives with whom I was later in contact, one of the first of many instances in which I unwittingly violated academia's own code of omertá. In hindsight, I suppose the sceptics believed I needed a speedy induction into the boot camp of American graduate school more than another intoxicating bout of independent study.

Nearly a half century has passed. I am proud to say I have never doubted my choice. My gratitude for it has only grown. In fact, it still brings a wistful shiver and memories of fleeting youth to recall my adventure finally drawing to its close, as shorter days of autumn darkened and nights in budget inns turned cold. Bidding farewell to Mediterranean color and light, I boarded a train in Barcelona. I visited friends in Basel and London. At October's end, I flew home.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025