My time on the Watson, the places I saw, the kindnesses I can never forget, and the sheer craziness of it merit their own essays and much more, a project perhaps for my fiftieth anniversary in 2027. I documented it diligently with over five thousand slides, several field notebooks and journals in the tiniest script, letters and postcards, and records of my rations that did honor to my dad's trade as a bookkeeper. Predictably perhaps, my focus soon loosened. After all, I could investigate other facets of saints' cults in classrooms and libraries, but such an unfettered opportunity for a firsthand look at monuments might not come again. Whatever my intellectual indiscipline, I never wavered in my determination, day after day, to reach churches and antiquities, the more distant and difficult, the better.

I could hardly pass up renowned ancient sites, like Paestum or Piazza Armerina, or those like Selinunte or Tindari that I had all to myself by the sea on breezy winter days with rolling clouds and raking light. Back in 1978, Spain's countryside offered ruins that sat in the open, unvisited and forlorn: the theatre at Ronda la Vieja, fortifications and a rock-cut church at Bobastro, or the Roman and Visigothic town of Valeria, to name just three. I reveled, though, in the multitudes of scarcely known medieval churches deep within forgotten regions like Abruzzo, Istria, or Asturias. Villagers were welcoming and inquisitive about the enterprising young American who trekked in with such enthusiasm to poke around their church. The Asturian parishioners whose church begged for repair thought—implausibly—I was a new priest sent to check it.

This twenty-year-old Bronxite didn't know how to drive, or even ride a bicycle. For my last seven months in Spain and Portugal, I hitchhiked when I could, walked when I had to, to arrive at dispersed rural sites. From Ponferrada in the Bierzo, I climbed, up and up the tortuous road, to the Mozarabic church of Santiago de Peñalba nestled in an amphitheatre of mountains where hermits once sought refuge. After an ambitious outing to the Romanesque church of Moraime by Galicia's remote Costa da Morte, I was stranded near Santa Comba, halfway back to Compostela, as night fell. Stoically, I marched over thirty kilometres, peering hopefully at milestones in pitch blackness to measure my steps. As I hobbled up to my room in the hours before dawn, young guests hanging out at the hostal just guessed I had been out carousing.

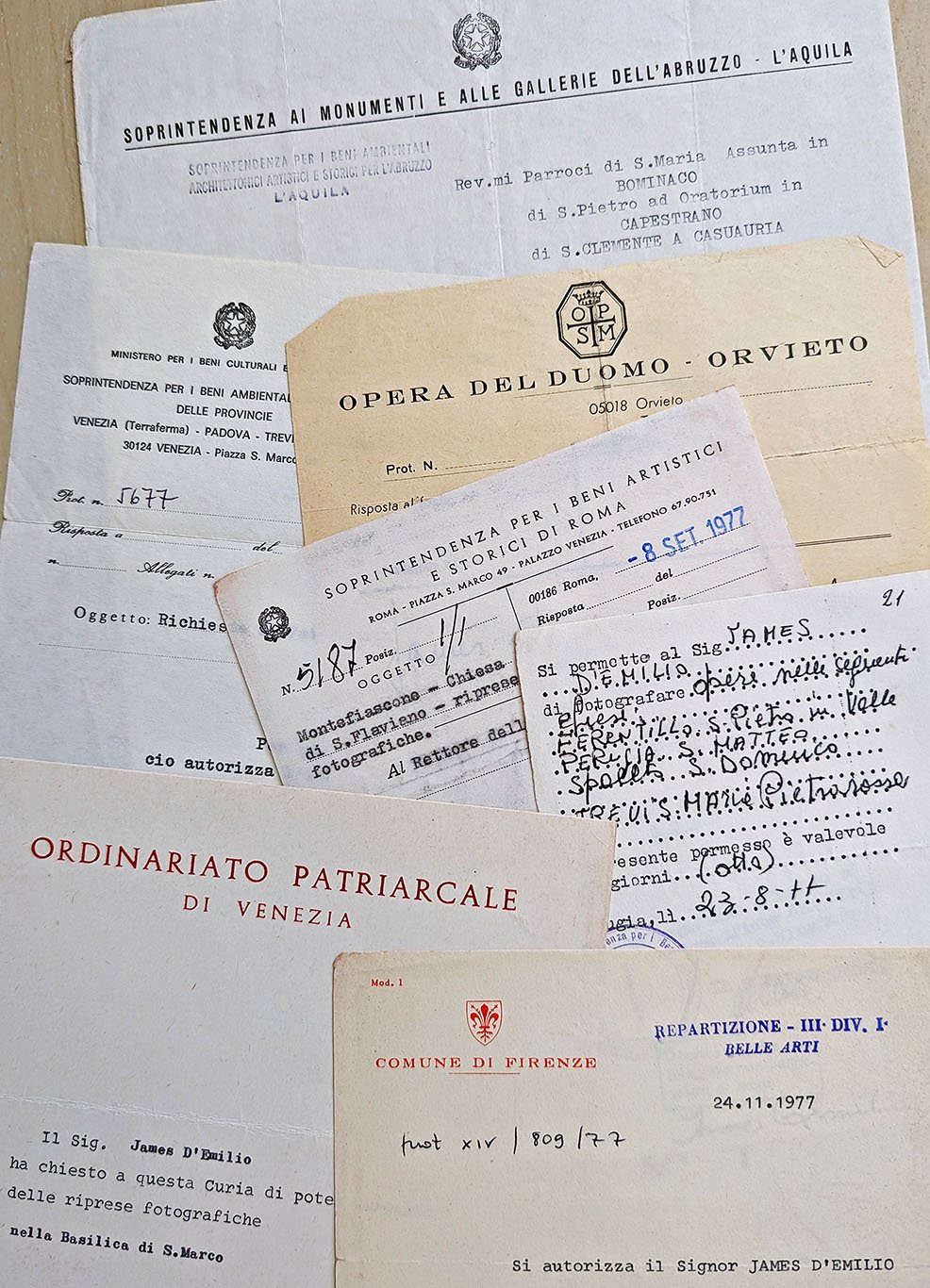

All year long, administrators of monuments made my work possible and joyfully memorable. The perplexed staff (but, what is it he's doing?) in the Soprintendenze and in offices of Italian dioceses and museums issued permissions and encouragement and ribbed me with good humor about the outsized gold seal my letter of introduction bore. Before video surveillance, I was trusted to be let in alone (and locked in!) at Santa Maria Antiqua in the Roman Forum and the Anagni Cathedral crypt. It meant a lot to me. Methodically, I picked my spots, set up the tripod, shot time exposures, and hoped for the best. The seconds for which I held a cable release—and my breath—were so many eternities, as I imprinted those hallowed spaces in my memory.

Fellow researchers and restorers gave advice, opened doors, and shared their contagious passion for this heritage. In my first dizzying days in Rome, Jack Freiberg guided me to the city's hidden layers of history and organized an excursion to Palestrina: meeting graduate students and hearing about their projects made the path ahead less intimidating and easier to envision. At the American Academy, David Levine tipped me off to the first-of-the-month viewing of Guido Reni's Aurora ceiling. With a worshipful rapture few saints could ever command, a small company of conoscenti gazed upwards in silence. A German researcher slipped me in secretly—and generously—to a warehouse of Roman and early medieval sculpture at Mérida. During his restoration, the architect Modugno showed me Sant'Angelo in Formis with justifiable pride and a palpable love of the basilica. Decked with a hardhat at Aguilar de Campoo, I saw the start of renovation at the former monastery where the Fundación Santa María la Real would rise as a center for Romanesque art and creator of the Enciclopedia del Románico. It may well have been the architect and cartoonist Peridis who chauffered me to nearby sites on a day that ended with sherry at Santa Eufemia de Cozuelos, a fabulous church on a private estate.

Officials regularly warned that they were but one link in a chain that depended on my resourcefulness and the cooperation of those I'd meet at the sites. On cue, a host of supporting characters gathered like saintly apparitions to assist me: priests and parishioners, farmers and truckers, veterinarians and laborers. Perhaps it was literally a saint, that lad on a white horse who rode up out of nowhere, saw me stumbling through a stony river bed—a shortcut, I was told—and pointed me towards the Sicilian church of SS Pietro e Paolo at Forza d'Agrò. Or those burly arms that held me suspended as I bounded off a bus in Messina, right in the path of a speeding car. Caravaggio's Raising of Lazarus would be a stunner any day, but that day was special.

At Summaga in the Veneto, the priest let me photograph frescoes minutes before a wedding. When the organ suddenly blared, I found myself trapped for the entire ceremony, crouching in embarrassment behind a lateral altar in plain view of the puzzled bride and groom. On that happy day, a few out-of-town guests took the surprise in stride, inspecting the art and amused to meet this ragged American, not dressed for any wedding, much less an Italian gala. Near Calvi in Campania, a farmer patiently gave detailed directions through the overgrown maze of tracks to the Grotta dei Santi. Sensing my despair, he assured me it was easy to find, if, he conceded, you knew where it was. While I was inside, a man stopped in, knelt, and prayed. A German couple took me along to Bominaco and San Pietro ad Oratorium in Abruzzo, and I made it to the isolated early medieval church of San Pedro de la Nave thanks to a Dutch couple who squeezed me in the back of their Citroen with a monstrously large and overly friendly dog.

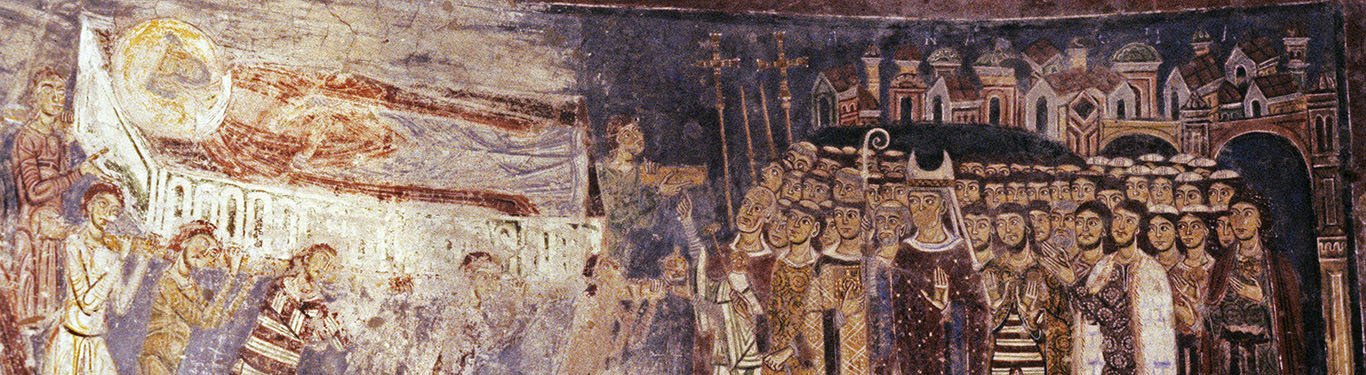

Sure, I was distracted by Doric temples and Baroque sensuousness, but medieval saints' cults held my travels together. Eighth-century inscriptions at San Silvestro in Rome were among my first photos: they listed feasts of saints whose relics had been deposited there. In Umbria and Lazio, I examined votive frescoes for clues—style, size, pigments, techniques—to levels of production. In predella panels, carved reliefs, or frescoes, I learned to see the permutations of recurring scenes in saints' lives as conversations among them. I rejoiced to find images of cult practices: the making of a shrine at San Vicente de Avila; or movements of relics at San Clemente a Casauria, Anagni Cathedral, and Venice's San Marco. I savored the pageantry of St Agatha's feast in Catania and arrived in Spain just in time to be enthralled by the Holy Week processions of Seville. In a grand finale, I made my way to St James's shrine at Compostela, like so many before me, visiting sites all along the fabled pilgrimage road.

Everywhere I went, I documented saints and their cults in medieval art and observed expressions of popular devotion. As marvels to admire and models to imitate, the saints came alive for me. Meeting them in every corner of medieval life, I came to understand their great congregation—local and international, old and new, women and men, royals and rustics—as a mirror of society and a marker of a cultural geography of regions, boundaries, and networks.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025