A cigar box of receipts and my white canvas bag I have kept as holy relics, but the Watson left other legacies. I surrendered to art history. The next year, I held a summer internship at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and headed to London with a Marshall Scholarship for a Masters program at the Courtauld Institute of Art. I intended it as a bridge to a PhD in History, but my project on Galician Romanesque sculpture spilled over into a dissertation. With the support of the Marshall Commission, I switched to the doctorate and spent a third year in London. In no hurry to leave Europe, I moved to Compostela, doing research for two years and tutoring students of all ages in English to fund it.

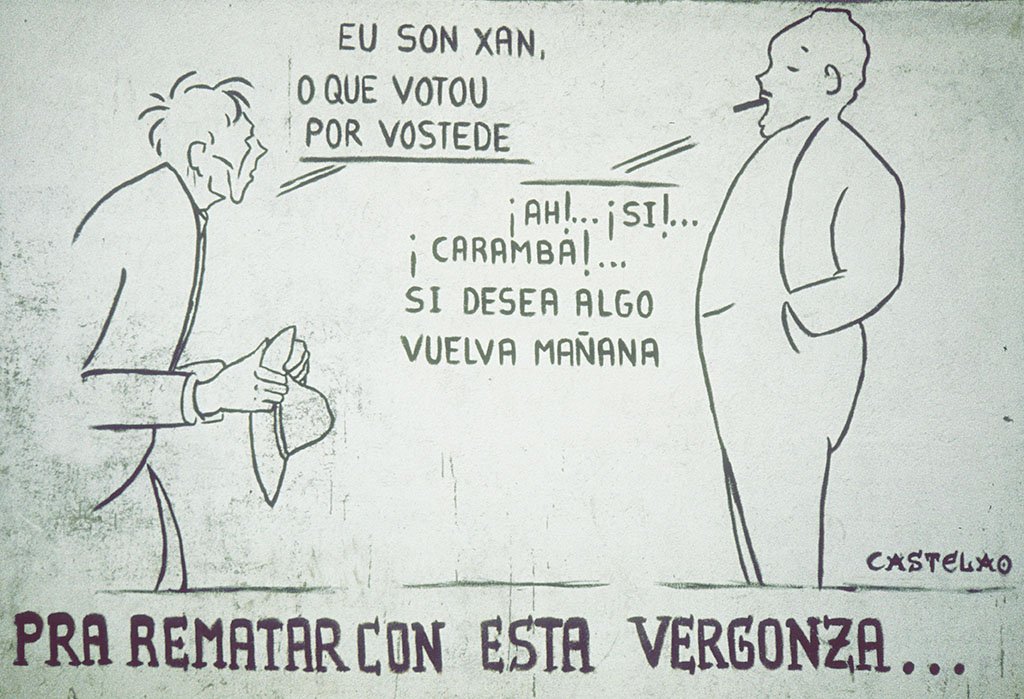

Despite my love of Italy, I had chosen Spain. A melting pot of cultures, its medieval heritage lay on the margins of the art history I knew. In the early twentieth century, pioneering studies by Vicente Lampérez and Manuel Gómez Moreno and a flurry of foreign interest had promised a bright future. But, the isolation and neglect of the Franco regime, and its stifling of scholarship and international exchange, took a heavy toll. With the dictator's demise, Spain's monuments seemed ripe for rediscovery. Miguel Angel García Guinea's monograph on the Romanesque art of Palencia proved it could be done. Fieldwork, though, was not easy: churches in towns were routinely locked, rural ones often isolated, rushed visits more closely monitored, photography discouraged, and viewing stymied by darkness, inattention, and tall, bolted rejas—a word I fast learned. In the depopulated mountains and meseta of northern Spain, railways were seldom near. Buses weren't going my way: they took villagers to towns in the morning and returned in the afternoon.

Recent history, ideology, and social practices magnified these logistical hurdles. I detected few signs of an infrastructure for maintaining or studying this patrimony. With other pressing needs, rural communities were especially disadvantaged. As an institution and as a place of worship, the church's role in modern Spain differed from Italy, and not in ways that facilitated a visitor's access. Busy priests shuttling among several village parishes and a distant diocesan seat were hard to track down; in their absence, those who might admit having keys were wary of admitting a stranger to a church. Artistic monuments counted for less in Spain's national imagination than in the home of Rome and the Renaissance. University faculties were parceled out in lordships whose lofty potentates might not abide a brash young foreigner disinclined to fealty. Nor had such a regime yielded a bountiful harvest of insightful studies or trustworthy editions. Across the political spectrum, perceptions of the United States were shaded, for different reasons, by our history of tortured relations with Spain and Latin America. In the surest measure of my utter naïveté, the sum of these challenges convinced me I was making exactly the right choice.

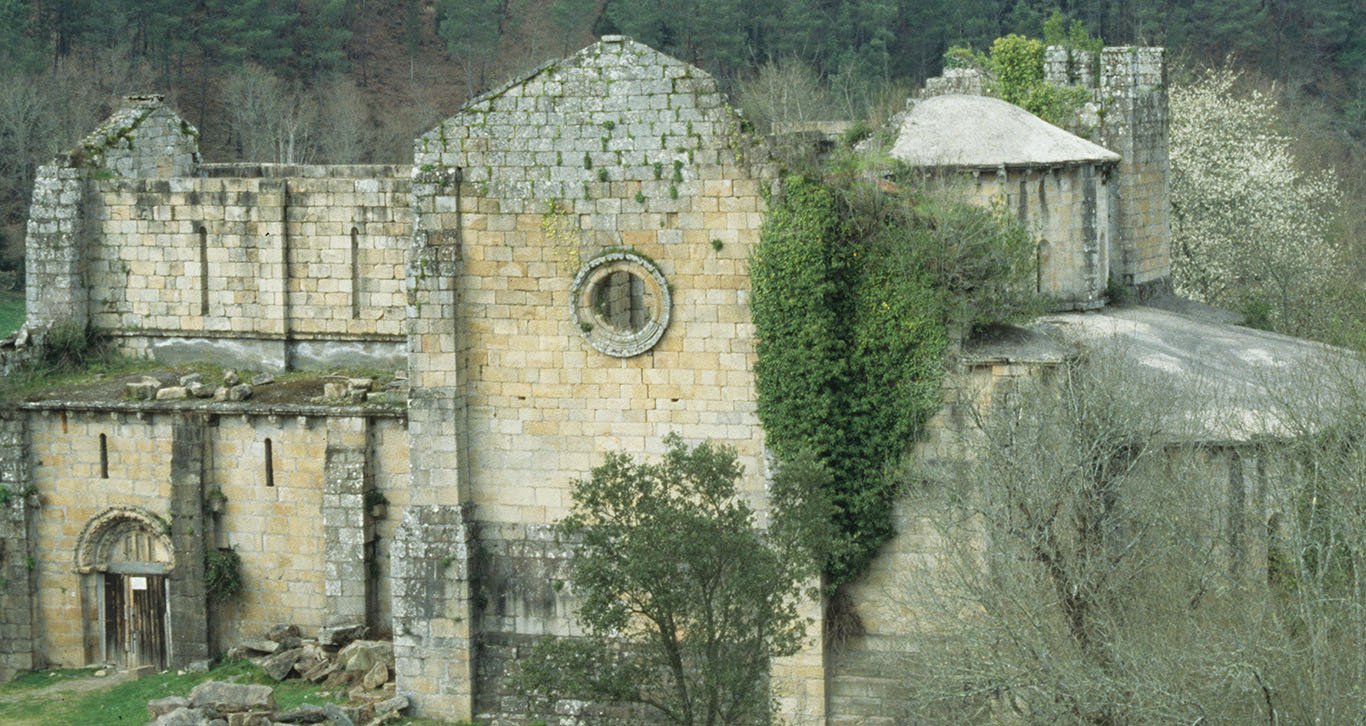

Within Spain, Galicia's beauty and remoteness seduced me as I was wrapping up my Watson year and considering graduate work. The hamlets and churches of its fractured topography exemplified the complexities of cultural geography that had absorbed me in Istria and the Alps, Umbria, Abruzzo, and Sicily. People I met spoke proudly of an awakening sense of identity and a language and culture long suppressed. In just three weeks, I surveyed medieval sites from Atlantic rías to the forested slopes and precipitous ravines of the Sil and Miño valleys. Besides four of five cathedrals and Cistercian monasteries at Oia and Oseira, I visited Santalla de Boveda, an enigmatic building of Roman origin; the early medieval churches of Santa Comba de Bande and Celanova; others with elements of that epoch (Atán, Santa Eufemia de Ambía, San Pedro de Rocas); and a dozen Romanesque ones (Moraime, Santa Cruz de Retorta, Bembibre, Eiré, Ferreira de Pantón, San Fiz de Cangas, Santo Estevo de Ribas de Sil, Xunqueira de Espadanedo, Xunqueira de Ambía, and those of Allariz).

I recite this honor roll for those of you lucky enough to know Galicia. You can comprehend what it was for a foreigner to tour them all in 1978 without a car and relying on tourist maps whose makers were baffled by these rural byways. From spare notices in the British Blue Guide to Mainland Spain, I could not have anticipated the intriguing inscriptions and curiosities of architecture and iconography this random sample would greet me with. It was barely an appetizer. Buildings named in passing in the Blue Guide hinted at the hidden wealth of that formidable terrain. Drivers, villagers, bartenders, and priests told of more churches everywhere. Here and there, I was teased with glimpses of spectacular ones I couldn't reach...yet: Diomondi and Santo Estevo de Ribas de Miño perched above the Miño and lit by the setting sun, or the Cistercian abbey at Meira beckoning me to return as I bounced by on a bus to Oviedo.

Return, I did, and many times. I met my future wife Ana, married in Vigo, and gained a second family. Anxo, Carmela and other friends I've been too careless of provided hospitality, long evenings of tapas, tazas, and conversation, and a sense of belonging in a foreign land. I found a mentor in Serafín Moralejo and sat in on one year's course in Compostela. Breathless from my hurried climb to the Facultad, I witnessed the thrilling spectacle of those lectures with the wide-eyed amazement of an out-of-body experience and the tingling intuition that this one-of-a-kind could never be equaled.

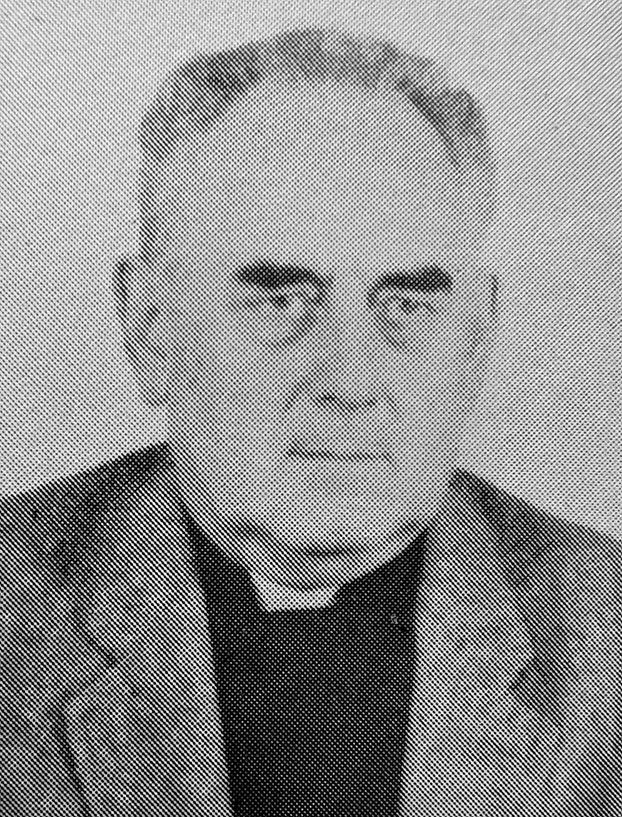

I was fortunate that D. Amador López Valcárcel was secretary to the bishop of Lugo. The stars aligned: we shared a birthday and a love of Galicia's churches and their communities. He was a man without airs, pretense, or officiousness: our first conversation, I remember, was about the difficulty of finding a pair of shoes that fit properly; our last about his thoughts in an earthquake that sent residents of Lugo into the streets. Lent a side desk in the diocesan office, I searched antiquarians' tomes enveloped in strains of classical music from Radio 2 and the aroma of his hand-rolled cigarettes. The help, information, and encouragement he offered were invaluable. Among the many priests I met, his name was golden, and for good reason. During opening hours, he patiently and perceptively handled problems and fielded questions from parish priests and other visitors about faith and conduct, and hardships of rural life that the responsible authorities ignored. I saw what it was to be a model clergyman, and what it was to live in villages too long disregarded.

Galicia's heritage did not disappoint. That trio of churches that had lured me from afar would star in my dissertation. The reports I'd heard were, if anything, understated: over eight hundred preserve something of a Romanesque fabric, scores are intact or nearly so. When I began, I did not yet know that modern Galicia had nearly four thousand parishes, mostly rural and dating from medieval times. Walking did not, in today's lingo, "maximize" research efficiency, but doing it until I learned to drive in 1988 earned the respect of the locals I met. I valued that. Those hikes gave me an intimate feel for the spread of habitation and human scale of distances in an abrupt terrain. At their measured pace, I took note of the inflections of a regional culture: vernacular architecture, crafts and materials, a roadside shrine, or the hearty breads of Cea and Escairón (those, I ate!). On the military maps I carried or the gravestones I read, names of countless localities recorded centuries, even millennia, of history.

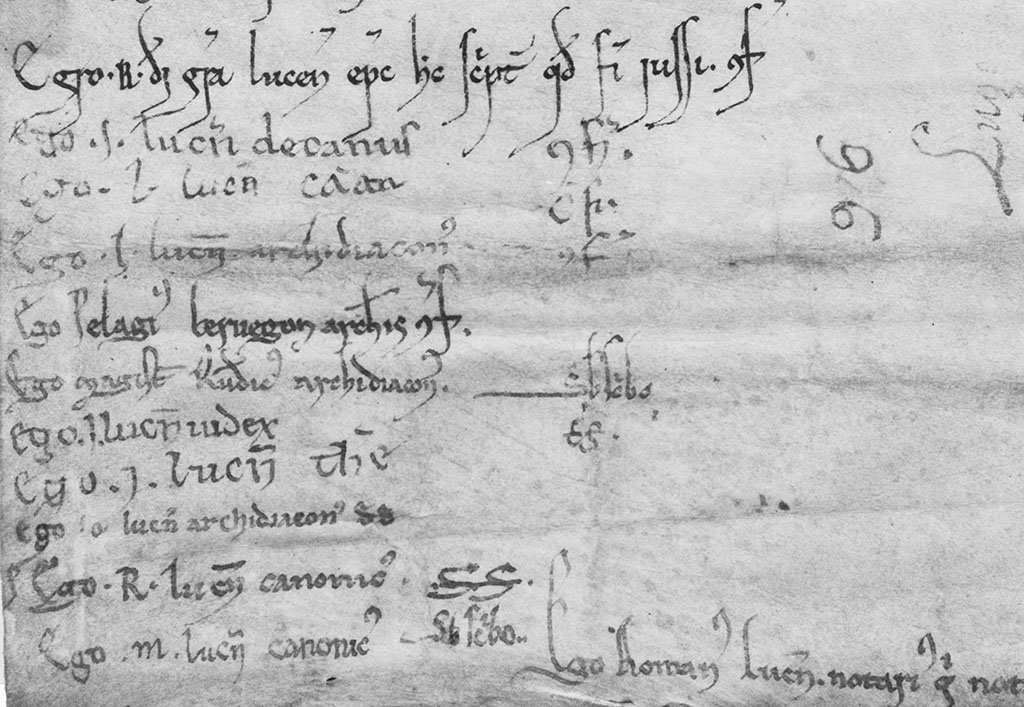

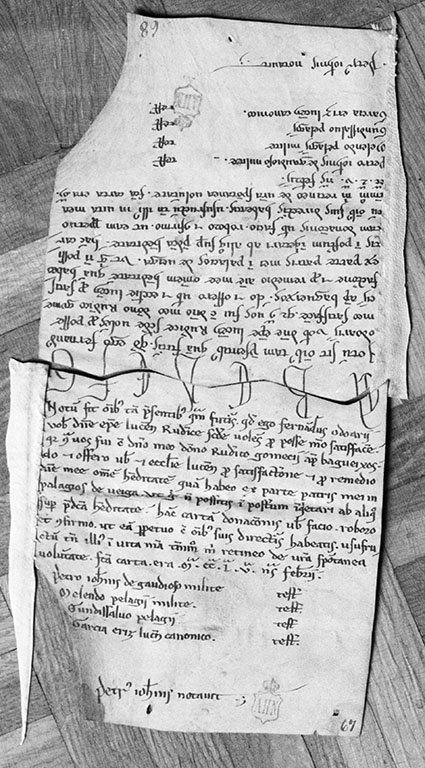

Archives, when open, opened up a new avenue of study. Initially, I imagined them as storehouses of data—the date or patrons of a church, for example. To prepare, I took a course on palaeography in London. I bristled at categories and terminology I thought overly burdensome for the job at hand: to read these scribbles. Once I held those brittle parchments and bundled papers in my trembling hands, they changed before my eyes. The charters were like the treasured objects I had once collected as a child. Belatedly, I was deeply grateful for Professor Julian Brown's remarkable instruction, and I remembered his lessons.

These documents had so much more to mine for meaning than the mere content of their texts: the size and preparation of a parchment, its layout and design, the idiosyncrasies of each scribe's hand and each day's effort, and the jottings from centuries of use and archiving. Along with the language and style of their texts, their physical form told stories of writing, literacy, and clerical culture.

I had come full circle. Seeing medieval art in situ and attending to non-figural ornament was freeing me from the tyranny of text-based interpretations that my background in classical and Christian literature had favored. Now, handling original documents brought their makers to life and turned handwritten texts into material and visual artifacts: what their words said was but one element, and not always the most important one, in a symphony of meanings.

Intellectually, Galicia was a sensible choice. Its Romanesque churches and plentiful ecclesiastical archives furnished an ideal laboratory for investigating a regional culture. Its location, landscape, and history invited one to explore its dynamic ties to the Atlantic seaboard, Europe, and the Mediterranean, and those between its own centers of power and more isolated districts of its rugged interior. Ambitiously, one might aim for the "total history" I had admired in the works of Marc Bloch, Fernand Braudel, and Georges Duby of the Annales school. Art history, I supposed, would hone the tools historians might lack to integrate the huge corpus of medieval architecture and sculpture into an interdisciplinary study of tradition and change in Galicia's layered history and culture.

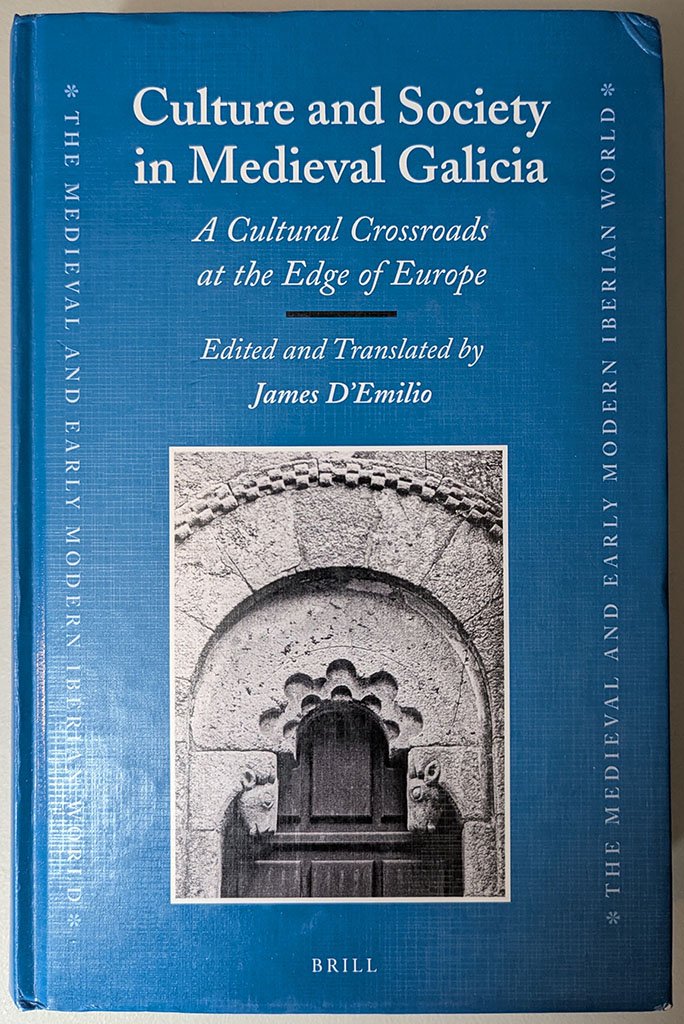

In my research and nearly twenty articles on cathedrals and monasteries, Romanesque churches and parishes, and charters and their scribes, I laid foundations for addressing these issues. With a team of twenty-two contributors, I tackled them directly in my edited volume, Culture and Society in Medieval Galicia: A Cultural Crossroads at the Edge of Europe (Brill, 2015). On this site, I am writing short prefaces to place my publications in that intellectual framework. I also reflect on the academic and professional challenges that selecting such a field entails. On my website on medieval Galicia, I am sharing the unpublished material I have amassed. Striving still for that elusive synthesis, I am tapping the capabilities of a medium I could not have foreseen to cap that strand of my long career with one last Atlantic sunset.

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025