What I was oblivious to, as I embarked hopefully on my research, were the social and institutional channels through which academic knowledge is produced, disseminated, received, evaluated, and shaped into a career. Spinning my master's project into a PhD made me an art historian with an odd specialty. What I boldly called sculpture was architectural ornament, dominated by foliage and abstract forms, boundaries blurred on blocks of rough-hewn granite. "So much junk!" as one smiling researcher summed it up, seeing my table at the Courtauld strewn with Ilford prints fresh from a day in the darkroom. Pieces were scattered among hundreds of village churches, complicating efforts to single out key monuments, contextualize examples, or create narratives for audiences likely to be unfamiliar with the material. Intended to lead to interdisciplinary study, mine was no savvy strategy for a terminal degree and career in art history.

More generally, medieval Spain still lay outside international purview in many fields in the 1980s. As for Galicia, Spaniards themselves tagged it as peripheral. Flocking to Madrid, Andalucia, and the Mediterranean, North American Hispanists preferred early modern and modern times. After bruising job interviews, medieval art historians of Spain—and the stray Byzantinist—swapped infuriating tales of being grilled sceptically about teaching a canon of northern European medieval art. We fumed uselessly, certain our competitors were never quizzed on Catalan painting or the Mezquita of Córdoba, Compostela or the Beatus manuscripts. Regardless of the region, the label "provincial" remained a liability in art history, even as the grip of elites and their culture was slipping in other areas of history. Spanish Galicia, decorative carving, and rural buildings: I had donned some infernal triple crown.

My dilemma was compounded by the jarring transition from a British program. I say so with no second thoughts. Through the Marshall Scholarship and Courtauld Institute, I gained remarkable intellectual opportunities and personal experiences. London's institutes and colleges had brilliant faculty and brought top scholars. I might hear lectures by Arnaldo Momigliano and Carlo Ginzburg or sit with fifteen students in a seminar led by Eric Hobsbawm and Emmanuel Le Roy Ladurie. The city was unparalleled as a cosmopolitan center for culture and the arts with inexhaustible layers of history, vast libraries and collections, and affordable concerts and plays. All of this fueled vibrant student life, friendships across diverse backgrounds, and a lifelong taste for south Asian food. Beyond London, I had easy access to the continent for my fieldwork. On visits to English cathedral towns and walks in the Cotswolds and Herefordshire, I practiced architectural photography and study. The Pevsner guides tutored me when Spain had nothing comparable.

That added up to a superb education, but, from the narrowest academic standpoint, my research-based doctorate lacked formal courses, comprehensive exams, or any teaching apprenticeship. I devised my dissertation topic on the Romanesque churches of Lugo with the same willful confidence that had led me to design my Medieval Studies major at Reed College. I did not derive my interest from seminars, a supervisor's suggestion, networks of colleagues, or the collaborative research groups that are widespread today. I had no idea how unusual that was. Nor did I grasp the benefits of well-established routes that connected newcomers with informed and receptive audiences, and supplied an ample bibliography of high-quality research, method, and theory to build upon. I might carp about the canon of art history, but it was a hub of scholarship and professional activity. That made its topics teachable, worthwhile for students learning the tools of the discipline, and advantageous to new faculty looking to integrate their research and teaching.

As a sojourner planning to return home, my headstrong insistence could be tolerated, for I was not on a career track. In fact, I was ignorant of the ways leading US programs facilitate their graduates' placement. With no professional pedigree, I needed such mentoring more than I would have recognized or chosen to accept. As I struggled on the job market, one American colleague sized up my plight with brutal and demeaning candor, "You must be having a tough time, no one here owes George [my PhD supervisor] a favor."

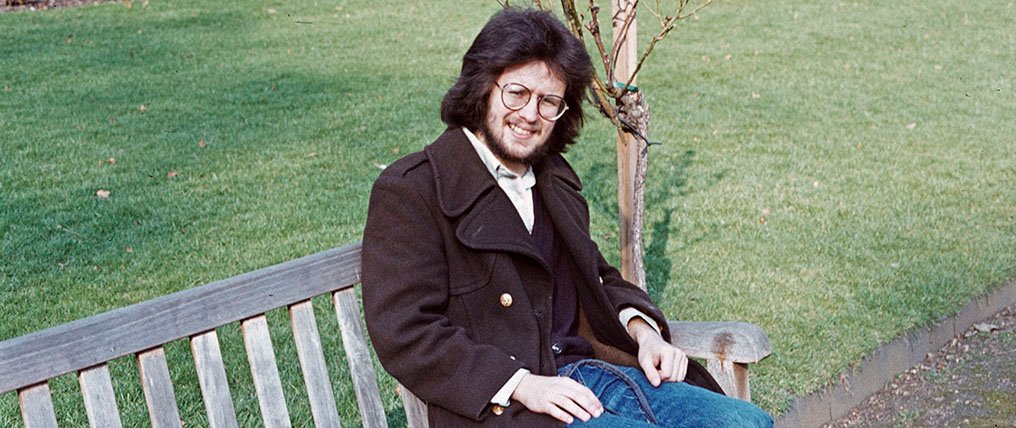

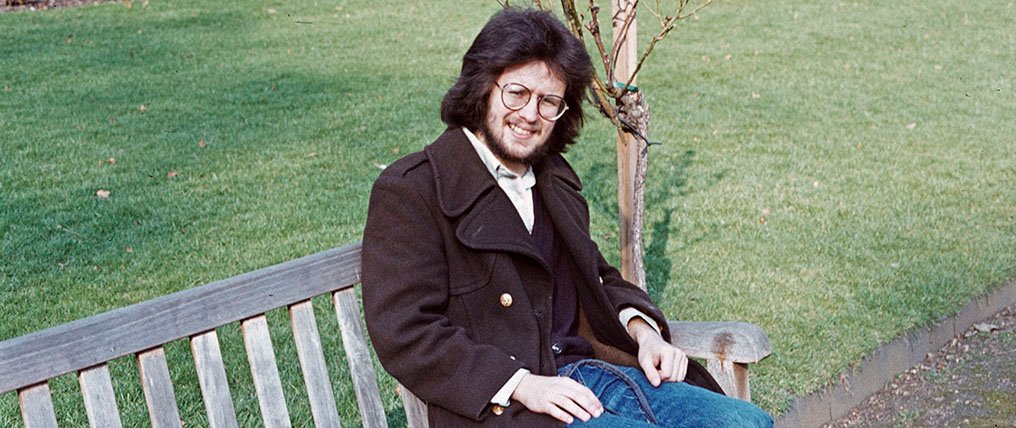

Copyright: James D'Emilio, who is the author of all texts and the author or owner of photographs, unless another source is acknowledged; last revised, May 2, 2025